University Grounds

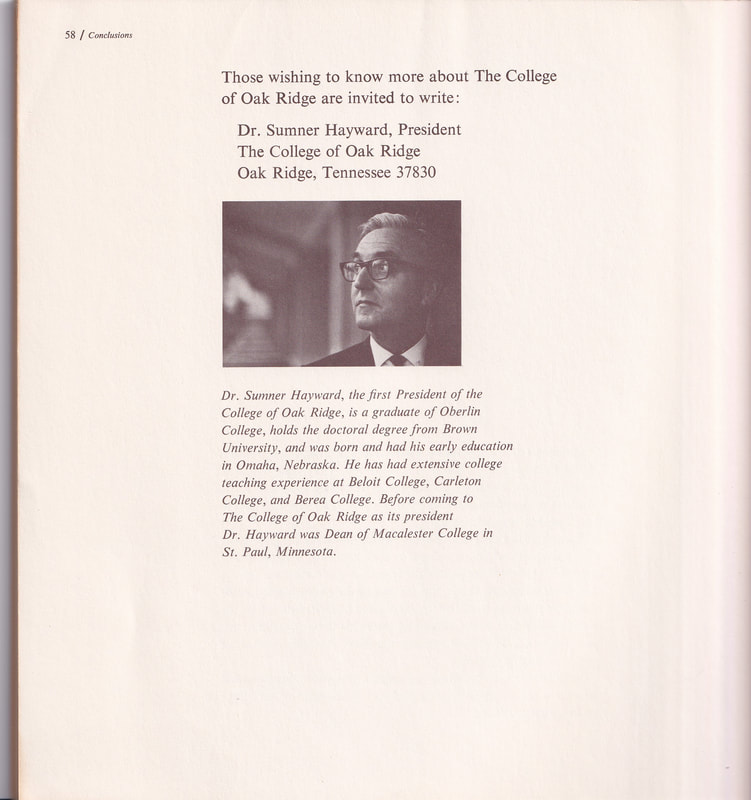

Menu

University grounds

|

I am always excited to be able to explore a new campus. But I will have to admit that in this case the enthusiasm was dampened by the knowledge that the institution I was getting to see for the first time will soon cease to exist. Fontbonne University is set to close just about a year after my visit. They made the announcement on March 11, 2024, that they will cease to operate at the end of the Summer 2025 term. The result of years of declining enrollment, its closure is one of many across the country. Dozens of colleges and universities have closed in recent years, and many more, like Fontbonne, are scheduled to close. Declining enrollment, the specter of the looming demographic cliff wherein we will see even fewer traditional high school graduates heading off to college, inflation, and a myriad of other issues have taken a toll on higher ed. As noted in my last post, I was in St. Louis and had some time to visit Washington University and given the close proximity of the two campuses I wanted to make sure to see Fontbonne while it is still Fontbonne. One of the few good things to come out of the university’s closing is that the campus will live on in some form or fashion. Washington University has agreed to purchase the campus. What exactly will come of the campus and its existing structures remains to be seen. The history of Fontbonne is robust and its roots go back a long way. As a post-secondary institution, 101 years have passed since the then-named Fontbonne College for Women enrolled its first students. The college was founded by the Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Joseph who had previously founded St. Joseph’s Academy, a school for girls, in 1840. I would imagine the college would not have come into being if the academy had not preceded it. Although covering the history of the two institutions is beyond the scope of this blog, suffice it to say that although the history of the university spans about a century, its roots go back further. The history of the Order extends more distantly. Founded in LePuy, France in 1650, the Sisters of Saint Joseph would do their works until the time of the French Revolution. The congregation would face forced disbandment during those tumultuous years but would be re-founded in 1808 by Mother St. John Fontbonne, from whom the name of the current university would take its name. I am not Catholic, but have more than an armchair understanding of the Catholic universities in the U.S. There are, of course, many and they have been founded by a number of different groups and orders. It is no different than the many different Baptist universities or other denominationally affiliated colleges and universities in that respect. You can lump them altogether for the sake of being affiliated with the Catholic Church, but in addition to institutional mission differences, they carry different flavors, if you will, thanks to their disparate identities. There are the Jesuit colleges and universities including such well known institutions as Boston College, Georgetown, Gonzaga, Xavier, and nearby Saint Louis University. There are twenty-eight Jesuit colleges in the U.S. and two hundred more in other countries around the world. There are Lasallian, or De La Salle Christian Brothers institutions like Christian Brothers University here in Memphis near where I live. There currently 181 colleges and universities which are part of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities in the U.S., and they have many different historical associations. Fontbonne and eight other existing colleges and universities across the U.S. were founded by the Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Joseph. I say currently existing, because the number has dwindled over the years. In 2023, Medaille University in Buffalo, NY, a college founded by the Sisters of Saint Joseph in 1937, permanently closed. It had transitioned to a non-sectarian institution some years earlier, so I suppose you could say it dropped from the list before it died altogether. Regardless, the list of colleges founded by the Sisters of Saint Joseph is small and will become smaller still when Fontbonne is shuttered next year. I refer the interested reader to two books which greatly aided in the creation of this post. First, take a look at Fontbonne at Fifty: A Nostalgic and Forward-looking Review of a Half Century of Fontbonne College, Clayton, Missouri, 1923-1973 by Sister Marie Vianney O'Reilly, C.S.J. Another great text is As Strong as the Granite: Vitality and Vision: Fontbonne at 75 by Sister Jane Kehoe Hassell, CS J, PhD. Both are good histories of Fontbonne and also provide some background information on the Order and its establishment in the region. The Sisters came to America from France at the request of Joseph Roasti, CM, the first Bishop of Saint Louis. He wrote to the Order in France requesting immigration of nuns trained in the education of the Deaf. After a long voyage, they were great by Bishop Rosati who escorted them to their future home. The Sisters settled in two homes, one in Cahokia, Illinois, and the other in the nascent town of Carondelet (now part of the greater St. Louis metropolitan area). The Cahokia location flooded and the Sisters there relocated to Carondelet. Their home there was a basic two-room log cabin with an attic that could only be accessed by a ladder on the outside. The Sisters established a school almost immediately. St. Joseph's Academy launched in 1840. The school was for girls and classes were held in the log cabin. In 1841, the school moved to a new structure in Carondelet, MO where the Mother House was located. Despite outbreaks, floods, the Civil War and all manner of occurrences, the region flourished. Saint Louis became a major hub for shipping and its population exploded. The Mother House would eventually be a large, grand structure. Before long, a number of colleges and universities began to spring up in the area. The Sisters believed that among their other good works was a need for the creation of a college for women. The late 1800's saw them slowly developing the foundation for what would become Fontbonne. St. Joseph’s Academy had been in existence for sixty-nine years when in a meeting on February 4, 1907, the Sisters held a brief meeting in which the decision to establish a college was made. The meeting minutes are simple: a motion was made, seconded, and approved. No moving speeches were made; no impassioned pleas were uttered. The Sisters had considered the issue for some time and when they were ready simply made the move to create a college. Their determination was firm, although support from others, including the Church, was not immediately received. Still, the Sisters moved forward. None the less, planning and development continued. The first portion of the campus consisted of 13.235 acres purchased in 1908 for $59,940 (more than $2 million in 2024 dollars). If you do the math, that’s almost $4,529 per acre (or better than $151,114 per acre in 2024 value). That is an incredibly large amount of money! A couple of months later, an additional 3.1 acres were acquired for $12,400 (or about $422,608 in 2024). Just where the Sisters of Joseph got such a hefty sum has been lost to history. Make no mistake, though, it was an extremely expensive acquisition. Having the land in hand, Sister Agnes Gonzaga, head of the local order and the prime advocate for the school, made repeated calls for support to establish the college. This included requests to the Vatican for permission to secure loans to start building. A positive response from Rome was not quickly given. One of the main concerns was funding. Despite having a fair amount of cash on hand and the ability to get loans, the Sisters were unable to get the approval of the Church to move forward. After nine years, the Sisters applied to the State of Missouri for a charter. It came quickly enough, being issues on April 23, 1917. In all likelihood, things may have moved faster thereafter if not for world events. Although World War I had been raging since 1914, the U.S. formally entered the conflict on April 6, 1917. The nation ramped up efforts to support the war effort and this undoubtedly impacted the ability to raise funds and develop things on the ground in Saint Louis. The following March saw the first cases of the Spanish flu in the U.S. Those first cases in Kansas would signal the oncoming one of the most devastating pandemics in history. The war would not end until that November, and the Spanish Flu would continue in earnest until 1920. As is frequently the case, a recession followed the end of the war. The Sisters were engaged in all manner of public service during these times. Still, the work to create the college continued. Finally, as the Roaring Twenties took off, so too did Fontbonne. By 1922, the college was organized and a curriculum developed. Classes would begin in September of 1923 with nine students and nine faculty members. Of the latter, six were Sisters of the Order. Since there was no campus to go along with the new institution, classes were held at St. Joesph's Academy and the students would live at the Mother House. Groundbreaking on the site purchased years earlier took place on April 14, 1924. Work on the original five campus buildings was going on simultaneously during the summer of 1924. It had to be quite the sight. After so many years of waiting, Fontbonne was literally sprouting out of the ground that summer like the flowers of spring. Modest though they were, the Sisters of Saint Joseph had to be beaming with some pride as the campus was, at long last, taking shape. When classes began for the fall term on September 18, 1925, they were held in the five new buildings on the campus for the first time. The buildings themselves would not be dedicated until October 15, 1926. The decision to dedicate the campus on that date was deliberate - it was the anniversary of the date in 1648 when the Sisters took on the Habit. Each of the five original buildings are clad in red granite and have Bedford limestone trim. The university's first commencement was held three years later on June 18, 1927. Eight women received their baccalaureate degrees that day. The college would grow for many years thereafter. Fontbonne admitted its first African American students in September, 1947. Initially a college for women only, Fontbonne would come to co-ed in time. The university lists 1971 as the year men were admitted to the institution in select departments, although men were allowed to attend non-degree courses in the evenings starting in 1955. Formal entry of men into all majors did not occur until 1974. The university did not begin offering graduate degrees until 1975 when in April of that year a master's degree in communication disorders was approved. Enrollment and the endowment grew over the years, but as is so often the case overall enrollment would plumet in recent years. Recent reports note that Fontbonne's enrollment is down more than 70% over ten years ago. In the end, it was just not sustainable. In the set below are two views of the university sign that sits on the hill overlooking the corner of Wydown Boulevard and South Big Bend Boulevard. In the background you can see Anheuser-Busch Hall on the right (see below) and the Jack C. Taylor Library (see below) on the left. As you can see, it was a wonderful day out during my visit. The set of photos below provides exterior and interior views of the East Building. The East Building is one of the original five buildings on campus, but it opened with a different name. It was Fine Arts Building, not to be confused with the current Fine Arts Building (see below). The first photo is the north façade of the building as seen from Wydown Boulevard. The Jack C. Taylor Library (see below) can be seen on the right in that picture. The second photo is the main entrance to the building on the west side of the structure. The following five photos are of the interior of the building on the first floor. The plaque seen in the sixth photo is in the back of the lobby area near the chairs seen in the fourth photo. I did some online sleuthing in an attempt to learn more about the Rosemary Leahy mentioned on the plaque. There are quite a number of Rosemary Leahy's out there, including a nun who was a member of the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Canada. But none of the ones I found information on were associated with Fontbonne, as far as I could tell, so I cannot say anything about her. If you know anything about her, please leave a comment. The final photo of this set is back to the exterior of the building on the south side of the structure. It is connected via a covered breezeway to Ryan Hall (see below) and the Dunham Student Activity Center (see below). The set below begins with a view of the main entrance to the Jack C. Taylor Library. The library was designed by the architectural firm Pistrui and Conrad (the firm would later be called Pistrui, Conrad and Gebauer), and if the reports available online are accurate William M. “Bill” Pistrui was the principal architect on the project. The building comes in at 39,000 square feet of space and was designed to hold up to 200,000 volumes. Construction and outfitting of the building came at a price of $1,225,700 (about $11.9 million in 2024 value). Groundbreaking for the library occurred on Valentine’s Day 1966, and it was dedicated on October 15, 1967. Although the other buildings on campus were open and some offices were occupied during my visit, the library was closed so I was not able to go inside to have a look around. There is a large amphitheater on the first floor which can seat 125 people. The area is called the Lewis Room in honor Mrs. Jame s A. Lewis, mother of Sister Mary Teresine Lewis, CSJ. Sister Mary came to Fontbonne in 1947 and stayed until 1974. She taught mathematics and was Dean of Students during her time at the university. When the library opened, the Lewis Room was noted as having gold colored carpet with green seating. I wanted to see if that was still the case but since it was closed I wasn't able to confirm it. The area in front of the library's entrance is called the Elanor Halloran Ferry Plaza. It is named in honor of Eleanor and Daniel Ferry. Mrs. Ferry is an alumnae of Fontbonne (Class of 1963) and her husband was Chair of the Fontbonne Board of Trustees. The area was once a green space extending to where the library currently sits. The plaza was named in honor of the Ferry’s on September 29, 2006 to recognize their endowing a scholarship for first generation students. Mr. Ferry, who passed on January 20, 2020 was a stockbroker who, in addition to being on Fontbonne's board, was President of the Missouri Athletic Club, President of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse, member of the Board of Directors for Catholic Charities, and a member of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem. In the Ferry Plaza in front of the Taylor Library is a statue called “The Founding Spirit”. The statue commemorates the Fontbonne 75th anniversary and the 350th anniversary of the Sisters of Saint Joseph. The piece is the work of Rudolph “Rudy” E. Torrini. Mr. Torrini was born in St. Louis in 1923 and serving in the Navy during World War II returned home and completed his undergraduate studies in art at Washington University in St. Louis. After completing his baccalaureate degree, he spent a year as a Fulbright Scholar at the Academia di Belle Arti de Firenza in Italy. He would later attend the University of Notre Dame where he completed his master’s degree under the direction of Ivan Meštrović. Regular readers of this blog may recall that Meštrović was the artist who created the statue of Pope Pius XII at nearby Saint Louis University. Torrini subsequently joined the faculty at Webster University where he stayed for seventeen years. He then moved to Fontbonne where he was the Chair of the Department of Art for an astounding thirty-five years. The Founding Spirit statue was unveiled in a ceremony in May 2000. Torrini passed away in 2018 aged 95. There was a different statue located in basically the same place in the past. I have uploaded a photo taken some time during the 1970's (I believe) which shows this statue. I believe the photo is public, but if not, I will gladly take it down for the copyright holder. The statue, seen in the last photo of this set, was called Our Lady and was installed in 1953. The piece stood 8' 3" without the base and was the work of St. Louis-based sculpture Hillis Arnold. Prior to its installation, a small pond was in the same location. Mr. Arnold was born in North Dakota on July 10, 1906. He contracted spinal meningitis as an infant and lost his hearing as a result. He graduated from the University of Minnesota (Class of 1933) with a degree in architecture. During his time there, he was awarded the Keppel Prize for sculpture. After graduating from Minnesota, he attended the Minneapolis School of Art. He would go on to be a professor of sculpture and ceramics at Lewis and Clark Community College (then known as Monticello College) in Godfrey, IL. He taught there for thirty-four years. Mr. Arnold passed away in 1988. I was not able to find out what happened to the piece, so if you happen to know anything about it, please leave a comment. I imagine the choice of his art was intentional not merely because he was known for Christian sculptures, but because he was Deaf. As noted above, the Sisters of St. Joseph came to America to teach Deaf children and Fontbonne's Deaf Education program is well known. The photos in the next set are all of Ryan Hall, Fontbonne's administration building. Ryan is named in honor of John D. Ryan who contributed greatly to the university. Mr. Ryan also happened to be the brother of Sister Agnes Gonzaga. Mr. Ryan passed away on February 11, 1933. When Fontbonne opened on the current campus, it was without residence halls. As noted above, when Fontbonne opened classes were held at St. Joseph's Academy and the students lived at the Mother House. Rather than having them continue to live there and commute to the new campus, accommodations were established in various buildings on campus. Students had dedicated quarters on the fourth floor of Ryan Hall, as well as the second and third floors of the East Building (old Fine Arts Building, see above) and the third floor of Anheuser-Busch Hall (then named the Science Building, see below). Ryan was open and I went inside to have a look around. My intention was to find the chapel and take some photos if it was not in use. I had read about the chapel prior to my visit and it is described as being quite grand. It has statues and alters made from marble from Pitrasanta, Italy. But as I wandered around the building I was greeted only by silence. I saw not a soul in the building and after a short time I began to wonder if I should be in there. Not wanting to be where I shouldn't, I left without ever having entered the chapel. The first photo is the front façade of the building which faces north. The second is the building's cornerstone which is also a time capsule containing among other things documents, a small bell, and a statue of Our Lady of Victory. The chapel extends from the part you see in the first photo southward as can be seen in the third and eighth photos. The interior shots here show the main floor hallway, two views of a mural on the first floor, and a cafe also located on the first floor. The next set of photos is Annheuser-Busch Hall. It is one of the five original buildings on campus, although it opened with the name Science Building. It was re-named on October 17, 2009 in appreciation for a $1 million gift the company gave to help renovate the building. Anheuser-Bush was a long time donor to Fontbonne, giving funds over the course of several decades. The building faces the East Building. Like East, it is also connected to Ryan via a covered walkway as seen in the second photo. Next is a set of photos of the Dunham Student Activity Center. Dunham takes its name in honor Meneve Dunham, Fontbonne's 12th president and the first lay leader of the university. She was inaugurated on October 16, 1985. Dunham was an alumnae of Clarke University (then known as Clarke College) in Dubuque, Iowa (Class of 1955). She went on to earn a master's degree at DePaul University and her doctorate at the University of Michigan. She returned to Clarke as an assistant professor. She spent some time at Tulane University, and returned to Clarke be their 13th president. The Meneve Dunham Award for Excellence in Teaching at Clarke is also named in her honor. She stayed in her position at Fontbonne for nine years, stepping down in 1994. She passed away on February 9, 2021 aged ninety. The construction of the building occurred during her presidency. It was completed in 1992 and was dedicated on March 4, 1993. The next set begins with two photos of Medaille Hall. Medaille is a dormitory designed to accommodate 100 residents. It was the first dorm on campus and as such a very welcome addition. The rooms are all individual, with pairs of rooms connected via a shared bathroom. That was a pretty forward-thinking design for 1946. Most dorms back then had shared rooms and communal bathrooms. The building is, of course, named after Jean Pierre Medaille, SJ. He co-founded the Sisters of St. Joseph with Bishop Henri de Maupas. Its sits just south of Ryan Hall. Older documents list the name of the green in front of the building as Medaille Meadow, but recent documents and the Fontbonne website refer to it as the Golden Meadow. I am not sure when or why it acquired this new name.The groundbreaking for Medaille occurred on July 16, 1946. It was formally dedicated on May 13, 1948. Reportedly, it only cost $300 to furnish Medaille in 1948. That is only about $3,910 in today's value. Given the size of the building, there is no way you could outfit such a space for so little today. I had spent a few hours walking around Washington University before going over to Fontbonne, and I will admit my feet were a bit tired. I looked to the south of Medaille and saw another building complex but decided not to walk down there. I regret that, as I have only this distant shot of the Fine Arts Building and Carondelet Hall complex from across a large parking lot (the third photo in this set). The building has had an interesting life, and unfortunately, I was not able to find sufficient information to precisely detail its past. It opened as a juniorate on July 29, 1960, but served in this capacity for only a short time. Fontbonne took over the space in 1968 and renovated it to become a dorm. It reopened in September 1969 in this capacity and was named Southwest Hall, a reflection of its location on campus. Apparently, demand for on-campus housing was limited and the building was underutilized. It was subsequently leased to neighboring Washington University in September 1975. It would acquire a new name twelve years later when it was dubbed Washington Hall in October 1987. I could not confirm it, but I think the name change was a reflection of Wash U's leasing the building. At some point, I assume when Wash U increased its own on-campus housing space, the building returned as a dorm for Fontbonne. It would see its name change again to Carondelet Hall in 2023 in honor of the Mother House and the university's centennial. I have even less information about the Fine Arts part of the building. At some point, possibly when it ceased being a dorm for Wash U, the arts moved into part of the building and that portion became the Fine Arts Building. I will do some more research and update this post if I find out anything. In the meantime, if you happen to know anything about it, please leave a comment. On the right in this photo, you can make out a brick wall which encloses the parking lot along Big Bend Boulevard. Just outside the entrance seen in the right foreground of the photo on the Big Bend side is the Fontbonne sign seen in the last photo of this set. I will close this post, as is most often the case, with a photo of Fontbonne's version of the near universal collegiate lamppost sign.

Fontbonne’s affiliation with the Catholic church had me thinking about the Book of Genesis from the Bible wherein God told Abraham that he would spare Sodom if ten righteous men could be found in the city. The need for many colleges and universities these days is for benefactors, whether they are righteous or merely generous individuals. I don’t know how many generous people it would have taken to keep Fontbonne afloat, but like Abraham the people of Fontbonne could not find the requisite number. So ends my visit and post. Farewell Fontbonne.

0 Comments

My oldest son had a jazz band competition at Murray State University this month, and I had the chance to tag along. I have never been on the campus, or even near it. Despite being in Kentucky on numerous occasions, I have never been to that particular area within the state. Its about a three and a half drive from our home in the Memphis area. The trip meant that in addition to getting to see his high school band play, as well as a number of others, I had about an hour and a half of down time. And for me, that means a chance to explore and photograph campus. I was not able to prep for the trip the way I generally do, and that meant I was walking around without the benefit of knowing anything about the campus or the university’s history. I was walking around rather directionless just taking it in. I was not sure what all I would see. It is not a terribly large campus and although I didn’t get photos of every single building or landmark on campus, I did see virtually all of it. I had a doctoral student who did his master’s work there, and although he spoke of his time there, we never discussed the campus. All of this to say that when I walked around it was totally spontaneous and I had no idea what to expect. Not a bad way to make a campus visit, just different than my usual method. After the fact, I read the book “The Finest Place We Know: A Centennial History of Murray State University, 1922-2022" by Robert L. Jackson, Sean J. McLaughlin, and Sarah Marie Owens (University of Kentucky Press, 2022) and it was very helpful in getting to know the university. I also found some online materials which helped in the preparation of this post. The university began life as the Murray State Normal School, a name it carried for only four years from 1922 to 1926. Normal schools, which I will discuss in some detail below, were colleges designed to train teachers. Reflecting that mission, the school changed its name in 1926 to the Murray State Normal School and Teachers College. That name, like the previous one, would last only four years. The “normal school” moniker would be dropped in 1930 making the name simply the Murray State Teachers College. It would carry this name for eighteen years. As was the case for most teacher’s colleges, the institution’s mission changed to be more encompassing, so in 1948 the name would change to Murray State College. By 1966, the institution had grown to the point of offering numerous degrees at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, so the name was changed once more to the current Murray State University. Today, Murray State has its main campus in Murray, KY, several satellite campuses, and a farm. The main campus covers just over 258 acres, and the institution enrolls about 9,500 students. It was a very sunny day, and the temperature was quite nice so during my break I explored the campus. Although distant from the mountains of eastern Kentucky, the campus is a bit hilly. It extends along a north-south axis with a newer development on the southern west side. The photos below generally follow my circuitous route around the campus. In the first set of photos, we have the Price Doyle Fine Arts Center. Price "Pop" Doyle was a professor of music at Murray State. He came to the university in 1930 and would serve as chair of the Department of Fine Arts from 1939 until 1957. That is a very long time to be a department chair! He was the inaugural chair of the department and served in that role until he retired from the university. The building is the tallest on campus. The building was dedicated on December 5, 1971. It is physically connected to the Old Fine Arts Building seen in the second photo. Old Fine Arts opened in 1945 and was completed without air conditioning. A significant fire broke out in the building in 1994 during a planned renovation. The third photo in this set is one of several gates dotting campus. The fourth is the Ordway Monument, the last remnants of Ordway Hall. Ordway opened in 1931 as a men's residence hall. The 31,000 square-foot building served in that capacity until 1972 when it was converted for use as office space. When I saw the old façade, I thought the building had been the victim of fire or some other calamity, but that was not the case. The building was simply razed in 2013. The final picture in this set is Ordway's original dedication plaque. Ordway's designer, G. Tandy Smith, Jr., was a prolific Paducah, KY based architect. He also designed the Pogue Library (see below) on campus. Many of his numerous structures are on the National Register of Historic Places. Included among these are the Johnson-Hach House in Clarksville, TN, the Kenmil Place House in Paducah, one of the many buildings in the downtown Princeton, KY Historic District, and the Pogue Library. The next set is of the Henry Lee Waterfield Library. When I first saw Waterfield, I didn’t think it was a library. It just didn’t look like a library to me, at least the back end of it. I don’t know why, since libraries can look like just about anything. As it turns out, it started life in a different role. It began life as the student union with essentially the same name. Instead of the Henry Lee Waterfield Library, it was known as the Henry Lee Waterfield Student Union Building. It opened in 1959 with all of the typical accoutrements of a student union: a bookstore, cafeteria, ballroom, recreation spaces, and a post office. It cost less than $1 million to build (just over $10.5 million in today’s value) and looked very different, at least from the front where the new addition stands today. You can see the older portion of the building in the third photo. The former side was an open “u” shape and long awnings covered the sidewalk and entryway to the building. The university’s collections had grown to the point that the existing space in the Pogue library were no longer sufficient. A decision was made to expand the existing building and convert it into a library while subsequently constructing a new student union. A groundbreaking ceremony for the renovation and expansion of the space took place on November 22, 1976, and the library took over the space in 1978. They had a dedication ceremony in the afternoon of September 2, 1978. It is named in honor of Murray alumnus (Class of 1932), former Kentucky Lieutenant Governor, state representative, Speaker of the House, businessman, and Murray State Board member (1969-1973) Harry Lee Waterfield. Interestingly, he served two terms as Lieutenant Governor, but they were nonconsecutive. The set below is of the combination structure that houses the Hutson School of Agriculture called the Oakley Applied Sciences Building. The building is named for Dr. Hugh Oakley. Oakley arrived on campus in 1946 having served in the Navy during Worl War II. He had been a public school teacher in Kentucky before the war. He came to Murray State to be the founding chair of the Department of Industrial Arts, a position he held from 1946 to 1965. He went on to be Dean of the School of Applied Sciences and Technology from 1965 to 1973 and subsequently served of the Dean of the College of Industry and Technology when the school changed names. He held that role until his retirement in 1977. The department had two interim homes until Oakley helped facilitate the purchase of three former military ordinance buildings in 1947. These surplus buildings were located in Illinois when purchased by the university. They were subsequently dismantled, shipped to Kentucky, and reassembled to create the since razed Industrial Arts Building. The current building was completed in early 1965 with the first classed being held there during the Summer 1965 session. The building would be renamed in Dr. Oakley's honor in a ceremony on April 25, 1992. Dr. Oakley passed away in December 2020 aged 88. As noted, in addition to industry and technology, the building is also home to the Hutson School of Agriculture. The school carries the Hutson name for good reason. A succession of Hutson's have contributed to Murray State since its earliest days. Nicholas Hutson was in the agriculture supply business at the time of Murray State's founding. He began the long tradition of Hutson family giving to the university. The family has given funds to start scholarships and various other causes and donated 160 acres for the university's lab farm. In thanks for these donations, the university named the school in their honor in 2010. The set below begins with three photos of John W. Carr Hall. The building is named for Murray State’s first AND third president, John Wesley Carr. You read that correctly, he was president twice in non-consecutive terms. Later in this post I will introduce you to Rainy T. Wells, the man most responsible for the university being located in Murray. Wells worked tirelessly to raise funds for the institution and lobbied hard to have it located in Calloway County. According to Jackson, et al., (2022), he expected to be awarded the presidency for his work. The state had other ideas and selected Carr. Jackson and colleagues (2022) report that Wells was “bitterly disappointed” but the two found respect for one another and eventually became friends. In a gesture of friendship and goodwill, Carr stepped down from the presidency to a dean’s position after a mere three years to let Wells have a turn. It’s difficult for me to imagine this to be the case. Perhaps I am jaded, but the idea of someone leaving a presidency out of goodwill seems like an impossibility. I would imagine a more likely scenario would be a resignation coming from the exasperation of having Wells scrutinizing every action or perhaps Wells engaging in a political maneuver of some sort to force Carr out. After all, Carr was (obviously) well qualified for the job. He was also older than Wells. Why step down? My cynicism may be misplaced and having no original research on the topic I will have to assume that Jackson, McLaughlin, and Owens (2022) accurately detail a most generous situation in which Carr stepped down to let Wells have a go at it. Whatever the motivation, Carr was both the first (1923-1926) and third (1933 to 1936) president of Murray State. Interestingly, after he stepped down as president the second time, he also returned to a dean role. Born in Indiana in 1859, Carr was a long-time teacher and school principal. After decades in these roles, he went on to earn his Ph.D. at New York University (Class of 1913) at the age of fifty-three. He then had a number of administrative positions before being selected for Murray State’s presidency. The building which carries his name was completed in 1937 at an expense of $240,000 (about $5.5 million in today’s value). It was the first dedicated gymnasium on campus, and it still serves in that role today. It opened with the name “Health Building”. Somewhere along the way the name changed first to the “Carr Health Building” and then to the present John W. Carr Hall. I was not able to find out when these changes occurred. The statue of Carr was placed in front of the building in 2020. Former Dean of Education Dr. Jack Rose and his wife Janice made the principal donation to fund the monument. The last two photos of this set are of the Blackburn Science Building which sits north of Oakley and northwest of Carr. The building, which I believe was originally called merely the Science Building, is named in honor of long-serving Murray faculty member and administrator Walter E. Blackburn. He arrived on campus as an instructor of chemistry sans a Ph.D. He completed his doctoral work at the University of Illinois (Class of 1944) while on faculty at Murray State. He rose through the ranks to be Chair of the Department of Chemistry and then, in 1968, Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences. Work on the building began in November 1947 and was completed in 1950 to the tune of $1,016,000 (or some $14.3 million today). A significant addition was undertaken in the 1960's which greatly enlarged the structure. This came with a $2,437,000 price tag (about $24.2 million in 2024 value). Dr. Blackburn passed away in 1974 and the building was re-named in his honor in 1975. The set below is of the Murray State student union, known as the Curris Center. The building is named in honor of Murray State’s seventh president, Dr. Constantine Curris. Curris was one of those presidents who moved around, serving in that role at several universities. He was president of Murray State from 1973 to 1983. He then jumped to Cedar Falls where he was the president of the University of Northern Iowa from 1983 until 1995 when he moved to take the presidency of Clemson University. He served in that role for only four years at which time he took over the presidency of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. He held the position there until 2008. The Curris Center comes in at 135,000-square-feet and was completed in 1981. Construction began in April 1978 and the structure was completed in five distinct sections to increase its stability in an earthquake. Curris was something of a bargain, costing only $8.2 million (or about $39.4 million today) to construct. The first photo is the southwest corner of the structure which also has a good view of one of Murray State's many lamppost signs (see below). The next four photos are of the west façade and courtyard. The university's athletic logo is prominently displayed in front of the main entrance on that side of the building and the Murray State shield can be seen just inside the building (sixth photo). The inside has the racehorse design you see in photos seven and eight. Interestingly, those silver horses and blue backgrounds are relatively new. There are photos online taken in 2012 which show those spaces to be bare brick. The light fixtures have also changed, going from large brown rectangles to the sleek white LED's you see in these photos (see here and here). I have to say I like the original version better than what is there today. Another entrance is on the lower level on the north side of the building. Just a few feet away is the statue of Racer 1 you see in photos nine through twelve. The final photo in this set was taken in the lobby of the lower level. A blue bench with a giant figure reading a newspaper. I thought it was neat. Next are two photos of the Collins Industry and Technology Center. When I saw the building, which sits across from the Curris Center, I judged it to be the older of the two buildings. To me, it looks like something from the 1970's, although some of its styling points are similar to Curris which could place it as a 1980's building. It actually opened in September 1991, and thus is quite a bit younger than Curris. It is named for Kentucky's first female governor, Marth Collins. Murray State has something rather unique about it, at least as far as public universities in the U.S. go. It is organized around residential colleges. Residential colleges are centered on a group of students and faculty located within a residential system. There are a number of colleges and universities in the U.S. which have them, although these tend to be at private institutions. Most people in the U.S. think of them schools in the Ivy League or at places in the U.K. like Cambridge and Oxford. They are the result of Murray State president Kern Alexander (more about him below). He introduced the residential college system to Murray State in 1997. Inspired by the English tradition, Alexander sought to provide a unique way to bring students into the Murray State fold by giving them residential associations (whether someone is an actual campus resident or a commuter) identity. He oversaw the process creating eight residential colleges: Clark, Elizabeth, Hart, Hester, Regents, Richmond, Springer-Franklin, and White. There are residence halls with the same names as the colleges (of course), most of which pre-date the residential college system. Each college has its own coat of arms (see the bit about lamppost signs near the end of this post), traditions, and activities. It is an interesting idea that the students at Murray State seem to value and enjoy. The first two photos in the next set are of the Elizabeth Hall and the Chestnut Pedestrian Bridge. There are more photos of the bridge below. It takes its name from the street over which it passes. The viaduct opened in 2023 and connects the main academic portion of the campus to the residential and athletics side to the north. In addition to allowing students to bypass traffic it removes the need to traverse two hills. The building gets its name from Elizabeth Harkless Woods, wife of Murray State's fourth president Ralph H. Woods. The building opened in 1964 and its style reflects that era. The building cost about $1 million to construct (about $10.3 million in 2024 dollars). It had the plain name "Women's Dormitory #2" when it opened. Woods was president of the university from 1945 to 1968, having the longest tenure in the role to date. He oversaw some of the most dramatic growth in the institution's history. Mrs. Woods passed away in 1976. I am uncertain as to when the building received her name. Of course, the residential college carries her name as well. The last two photos of this set are of the Hollis C. Franklin College residence hall. It is one of the newer buildings on campus. It opened in September 2016. It is named in honor of its Marion, KY namesake, who was a banker and a long serving Murray State Board of Regents (1947-1956) member. It is actually the second building to carry this name. The original Franklin Hall opened in 1963 and was also a dorm. The older Frankling remained in-place and in-use during the construction of the new building. The new Frankin College building is considerably larger than the previous one. Old Franklin housed 330 students, whereas the new building houses 380. But it is not merely the addition of 50 beds that makes the building larger. Owing to a more modern style, the building affords its residents with more personal space. There are also more lounge and study areas in the new structure as well as a large meeting space that can hold 100 people. The set below begins with three photos of the George S. Hart residence hall, home to the eponymously named residential college. As I approached the building, I thought it was merely one of those 1960's or 1970's style dorms that dot most American colleges: tall, plain, and utilitarian. For the most this is the case, but as I got closer I could see the neat exteriors on each end. Not exactly Gothic cathedral-style elegance, but they are neat additions to an otherwise Brutalist box. George S. Hart was born in Calloway County on March 1, 1893. he served in the Army during World War I, risking to the rank of Sargeant Major. After the war, he returned to Murray where he would leave an indelible mark on the community. Hart was mayor for twenty years and was president of the Bank of Murray. He was a long-serving member of the Murray State Board of Trustees. I was not able to find out too much about the building. I believe it opened in 1966, although I may be mistaken. I am also fairly certain the building has carried Hart's name since it opened, although again this may not be the case. The seven-story structure has space for 534 residents. The fourth photo shows the Winslow Dining Hall (foreground) and Lee Clark Hall, home to Lee Clark Residential College (background). The Winslow Dining Hall opened in 1964. I was unable to find out anything about the building or its name. Lee Clark was a major force behind getting the university located in Murray. He was involved in business and farming in nearby Lynn Grove, KY. He was also a state representative. During his time in the statehouse in Frankfurt, he lobbied hard for the western part of the state in general and in particular for the college. History has it that he could have easily moved on to be a congressman, but he held no interest in the job. Instead, he went to work at Murray State. He was the superintendent of buildings for a time as well as the manager of the bookstore. He was also a seventeen-year member of the university's Board of Regents. The current building is the second to carry his name. The first, also a dorm, opened in 1962 and has since been razed. Given their near identical outward appearance, I assume the building opened around the same time as Richmond Hall (see below) which occurred in 2009. The fifth photo shows Hester Hall (foreground) which is the home to the Hester Residential College and the James H. Richmond Hall, home to the Richmond College Residential College. Hester is named in honor of long-serving Murray State Registrar Cleo Gillis Hester. She worked in the registrar's office from 1927 to 1960! I'm not certain when the building opened, but it looks the part of a 1960's or 1970's structure. I may very well be mistaken about this since the Hester Residential College did not come into being until 1996. The building may date from then as well. The eight-story structure is mixed gender. Like Clark, the James H. Richmond Hall is relatively new. The building is named in honor of Murray State's fourth president. Richmond was born in the rural community of Ewing, Virginia, a few miles from both the Kentucky and Tennessee borders. It is the second dorm to carry the Richmond name. The original structure opened in 1960 and housed up to 242 residents. The 45,912 square-foot building was demolished beginning in late December 2019. The new (current) Richmond opened ten years earlier in 2009 and houses up to 270 students. The building was extensively damaged by an explosion on June 28, 2017. A physical plant employee had run over a natural gas line regulator that morning setting the stage for the explosion later that afternoon. The building was largely vacant thanks to it being summer. No one was killed in the incident although one employee was injured. None the less, the south wing of the building, which is what you see in this photo, experienced significant damage. Two floors were largely destroyed. The building was repaired at an expense of $13 million (about $16.6 million in 2024 dollars) and re-opened in 2019. Finally, this set concludes with a photo of the collection of buildings known as the College Courts. The buildings make up 132 apartments across twelve structures. The first photo below is the relatively new Susan E. Bauernfeind Student Recreation and Wellness Center. The building opened in 2005, although it looks much younger. It is quite large considering the number of students at Murray State. It has three basketball courts, an indoor track, racquetball courts, exercise facilities, recreational space, and two pools. Alumnus Arthur J. Bauernfeind (Class of 1960) and his wife Diana made a substantial donation to build the center which is named in honor of their late daughter. He is the former CEO of Westfield Capital Management and former member and chair of the Murray State Board of Trustees. The last two photos of this set are of the Chestnut Pedestrian Bridge looking south toward the Curris Center. They were taken a few minutes apart during and then after a change in classes. The first photo in this set is Faculty Hall. I was not actually able to find out anything about the building online nor in my reference material or the book by Jackson, McLaughlin, and Owens. It is a fairly typical looking campus tower which houses the College of Humanities and Fine Arts. If you happen to know anything about it, please leave a comment. The last two photos of this set are of Alexander Hall, home to Murray State's College of Education and Human Services. Alexander Hall is named for Murray State’s 9th president, Kern Alexander. He came to Murray State in 1994 and stayed in the position until 2001. In a weird feat generally not seen outside of politics, he was succeeded in the presidency by his son F. (Fieldon) King Alexander. Before I delve into that fact, it leaves me with two questions: (1) how many people have served as a college president who had a child go on to serve as a college president? and (2) how many times has that been at the same university? I would venture a guess that this is one of the few times where a child not only followed in their parent’s footsteps but did so at the same university and immediately after their parent. Kern Alexander was born in 1939 in the small community of Marrowbone, Kentucky. He completed his undergraduate work at Centre College (Class of 1961), and then went on to earn a master’s degree at Western Kentucky University (Class of 1962) and an Ed.D. from Indiana University (Class of 1965). Having served on faculty at a number of universities, he was the 7th president of his alma mater Western Kentucky from 1986 to 1988. He established WKU’s community college during his brief presidency. His time there was notable for both controversies and his short tenure in the position (one being part of the other). As for his son, F. King Alexander was hired as Murray State’s president in a move that itself was described as controversial. The board of regents conducted the search in a less than open manner, serving as the search committee and the final approving authority for the hire. The faculty senate at Murray was none too pleased by that fact. It was during his tenure that Alexander Hall was built as was the Susan E. Bauernfeind Student Recreation and Wellness Center (see above). He left Murray to serve as president of California State University Long Beach, Louisiana State University, and Oregon State University. His hire at LSU was contentious, with the faculty senate there making a vote of no confidence in him which he withstood. His time at LSU would haunt him, however. His handling of multiple sexual assault cases at LSU resulted in the Oregon State faculty senate issuing a vote of no confidence in him as well. This time, the vote and the outrage in his handling of those cases resulted in his stepping down about a year into his tenure in Corvallis. The photos in the next set are of a newer complex of buildings on the west side of campus. The complex sits just south of Alexander Hall. Collectively, these buildings make up the Dr. Gene W. Ray Science Campus. Ray, a Murray State alumnus (Class of 1960) went to my alma mater the University of Tennessee for his master's in physics (Class of 1962) and his Ph.D. in theoretical physics (Class of 1965). The founder of the Titan Corporation, Ray was involved in the IT world in one form or fashion for most of his career. He and wife Taffin have given generously to Murray State over the years including a major gift to establish the Gene W. Ray Center for Racer Basketball. When the science campus opened in 2013 it was named in his honor. He passed away on July 28, 2023. The buildings on the Ray Campus and the units they contain are part of the Jesse D. Jones College of Science, Engineering, and Technology. Jones hailed from Marshall County, Kentucky, and attended Murray State as a nontraditional student. He was married and had two kids at the time and worked a night shift during his college years. He graduated with his bachelor's in chemistry and mathematics (Class of 1964). Life took him to Baton Rouge, Louisiana after graduation where he had a successful career in plastics. The part of the structure on the right is the Biology Building. The building on the left is the Jesse D. Jones Chemistry Building. The clock, prominent in the middle of the complex, is named for Jones' father Jesse L. Jones. The next set beings with photos of the front and back of Rainey T. Wells Hall. Wells is an important figure in Murray State history and is considered the person most responsible for te institution being located in Murray. Wells was born in Calloway County just outside of Murray in 1875. He received a bachelor's and master's degree from Southern Normal College in Huntingdon, TN. I will admit that I had never heard of that institution prior to reading about Wells. My initial sleuthing provided me with no information about the school. There is a Wikipedia page listing nine graduates of the institution (see here), as well as a page on a Tennessee genealogy page listing still more alumni (see here). As for information on the college itself, I have not found anything so far. There were other similarly named institutions and many small normal schools which have long since ceased operations for which information can be easily found, but the Southern Normal College is not among them. If you know anything about the institution, please leave a comment. I will either update this post or create a new one if I am able to uncover anything. But, back to Wells. After completing his studies in Tennessee, Wells returned to Calloway County where he founded the Calloway Normal School in 1899 in the town of Kirksey. He was only twenty-four at the time. Somewhere along the line, Wells must have "read the law" as they say. This was a common historical practice whereby you could become an attorney by studying the law and taking an exam without actually having to go to law school. He began work as an attorney in 1901. Another aside, I had never heard of the Calloway Normal School until reading about Wells either. The school continued for more than a decade after his departure but eventually closed in 1913. After his departure, he was elected to the Kentucky legislature and later became the tax commissioner for state. His experience with the normal school and his involvement in politics and government would serve him well in the effort to locate a new public college in Murray. The early 20th Century was a time of expansion in the number of colleges in the U.S. Building on the foundation of the many Land Grant institutions created in the mid- and late-1800's, a new array of state supported colleges began to dot the landscape. Many of these were normal schools, colleges created for the purpose of training teachers. The name "Normal School" is derived from St. Jean-Baptiste de La Salle's model for teacher's colleges. He established the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools in 1685 in France. The institution worked on the basis of teaching "normal" classroom values and behaviors to students. This process, the École normale in French, was subsequently used as the descriptor of teacher's colleges for hundreds of years thereafter. Indeed, the University of Memphis where I work was established as a normal school. As K-12 education evolved, many states recognized the need for more robust teacher training and a boom in the establishment of new normal schools began. Kentucky had established two such institutions in 1906 - today's Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green and Eastern Kentucky University in Richmond. In 1921, the state decided to add an additional normal school in the western portion of the state. As was frequently the case, many communities vied for the opportunity to have the school located in their town. The state's Educational Commission received bids from numerous cities and towns. Wells sought to have the new school located in Murray. His efforts would prove crucial. Wells understood education; he had trained in a normal school and had founded and led such an institution. He also understood government and finance. As a politician, he knew how to rally people to a cause and the personality and presence to motivate people to action. He went to work immediately to secure the school for his hometown. He led the campaign which saw the community raise $117,000 (about $2 million in today's value). Some 1,352 people in the area donated to the cause. The funds would be given to acquire the land and support the construction of the first building for the new school. He rallied the community to support the effort by providing lodging space for students so that instruction could begin without the need for dorms. These efforts placed Murray head and shoulders above the competing towns and on September 7, 1922, the state officially chose it for the location of the new school. Things continued to move quickly. Wells and others worked to ensure the school's opening only one year later. The first 87 students matriculated in the Fall of 1923. Since insufficient time had passed for the creation of the campus, a temporary location was needed. Wells had worked out an agreement with the local school district to use classrooms in the high school. The first building on campus would open the following September. Wells had a part in most things during those years and was instrumental in the selection and hiring of the first president, Dr. John Wesley Carr (see above). He would serve as Murray State's second president from 1926 to 1932. After leaving that role, he became legal counsel for the insurance firm Woodmen of the World in Omaha, Nebraska. He retired home to Murray in 1947 and passed away in 1958. Wells opened as a dorm for women in 1925 and had space for 316 residents. It was later enlarged to have its own cafeteria and an infirmary. I am not sure when it was converted, but it is no longer a dorm. Today, the Department of Psychology and some other units occupy the building. Next, we have the Business Building, home to the Arthur Bauernfeind College of Business. As noted above, Bauernfeind and his wife Diana are long-time benefactors to the university. The college of business began life as the Department of Commerce and did not become a free-standing unit until 1965. Thomas Hogancamp, who joined the department as a faculty member in 1948 and would later become chair in 1952, was the college’s inaugural dean. In the past, the building or buildings that house the business school on any given campus was just that – another building on campus. Sure, I like to look at all campus buildings and if something is interesting or notable in appearance or for some other reason, I make sure to cover it here in my blog. But something occurred to me during this visit which has not happened before. I am completing my master’s degree in management this semester at Austin Peay State University. As I was walking across Murray State and saw the business building, I thought “I wonder how they compare to us?”. It is a question I have asked myself before, but never with regard to a college of business. I imagine I will now have that question on my mind on every subsequent campus visit. Business buildings are often one of the nicer buildings on campus owing to the fact that business school alumni tend to give considerable amounts to their alma mater’s. The next set is of the Forrest C. Pogue Special Collections Library. When the building opened, it was known simply as the Library. The building is named for Pogue, a Murray alumnus (Class of 1931), noted historian, and one-time faculty member. After completing his undergraduate studies at Murray, Pogue went on to earn his master’s degree at the University of Kentucky and his Ph.D. at Clark University. He subsequently returned to Murray as a member of the history department. He was drafted in 1942 and after a year as a grunt in training, he was reassigned to be a combat historian, a role much more suited to a man in his thirties with a Ph.D. in history. He deployed to England and then to France after D-Day. Part of his work involved interviewing wounded soldiers in field hospitals. He was awarded the Bronze Star and the Coix de Guerre during the war. After separating from the Army in 1945, he was hired as a civilian historian to continue his work. General Eisenhower chose him to write the official history of the European campaign, resulting in the book United States Army in World War II: European Theater of Operations: Th Supreme Command. He returned to Murray for a time in 1954 but left to continue his work at the George C. Marshall Research Foundation in Virginia. He continued to be a prominent military historian until his retirement in 1984. The university named the library in his honor in 1978. He donated his books and his personal papers and other items to the library in 1989. The building was completed in 1931. The set below begins with views of the west façade from the quad. On the right of the first photo is an unusual sight – the remnants of a tree covered with shoes. A tradition began in 1965 that Murray students and alums would nail a pair of shoes to the tree upon marriage. The pair would add one shoe for each partner. Some even return to add baby shoes upon the birth of a child. The tree apparently died at some point, but the tradition lives on. On the left of that photo, and subsequently in the next four photos in detail is a statue of Rainy T. Wells. The piece was created by artist Edward T. Breathitt III. An alumnus of American University, Breathitt is the son of former Kentucky governor Edward T. “Ned” Breathitt II. The piece was completed in 1997. Breathitt completed a statue of his father which is located in Hopkinsville, KY, the late governor’s hometown. Close-ups of the main entrance on the west side follow in photos six through eight. I love the intricate metalwork and windows. The doors are bronze and quite heavy. Apparently, there was some concern about their cost when the building was constructed. Rumors swelled that they were gold, not bronze, and that they cost $40,000! That would be about $751,000 in 2024 value. The cost was not that extreme, but the doors did come in at an expense of $14,000 (about $262,855 today). That is still a hefty sum. The building was completed in 1931 during the Great Depression. Given this context, it is not surprising that spending over a quarter of a million dollars on doors would be seen as extravagant and problematic. The lights are also really nice. Photo nine was taken just inside that doorway. The last two photos were taken on the opposite side of the building. The library has its own sub-library in the form of the James O. Overby Law Library. It received the name in 1997. Overby completed his law degree at the University of Kentucky (Class of 1940). He served as General Counsel for Murray for years. The last photo is the east façade entrance. Again, I love the metalwork, windows, and light fixtures. Pogue was the eighth building to be constructed on campus and the first dedicated library. The first two photos of the next set are of the Lowry Center (on the left) and Wilson Hall as viewed from across the quad. Lowry is named for the colorful Clifton C.S. Lowry who was a professor at Murray State for forty-three years. He was known to be a demanding professor who pushed his students to do their best. He joined the faculty in 1925 and retired in 1968. The building is connected to the Pogue Library and was for a long time called the Lowry Library Annex. The building opened in 1967. I am not sure when it acquired the Lowry name. Given the building’s construction in the early 1920’s and the popularity of the former president at the time, you might think that Wilson gets its name from Woodrow Wilson. But the honor is actually to James F. Wilson, a member of the Murray Board of Regents. Wilson was the second building constructed on the campus. It opened with the very plain name of “Classroom Building” but as is often the case for new colleges, the building served many purposes. For a time, the library was housed on the third floor. The university’s first gym occupied the first floor. I suppose when you are dealing with an institution that is less than two years old you don’t have many options in terms of giving a building a notable name. The name was changed to the Liberal Arts Building at some point and eventually Wilson. I was not able to find out when that change occurred. Like most older campus buildings, many things have moved in and out of the space over the years. The third photo shows the east side of Lowry as seen from 15th Street. The fourth and fifth photos show the lovely entrance to Wilson on the south side of the building. The sixth, seventh, and eighth photos show the Price Doyle Fine Arts Center on the right and the Lovett Auditorium on the left. Lovett was where my son's jazz band competition was being held. Lovett looks small compared to Doyle, but the view is deceiving. The auditorium has seating for 3,000 on two levels. When it opened in 1928, it was the largest theater in Kentucky. For nine years, it was the home of the Murray State basketball team. They would move out in 1937 when Carr Hall opened. The building is named in honor of Rainey Wells daughter Laurine Wells Lovett, herself a member of the Murray State Board. The ninth photo also shows Faculty Hall on the left. The inside of the auditorium is quite nice despite its age and some deferred maintenance. I took some photos of it but decided not to publish them here since there were high school students there. It is a very nice place to hear a concert, and I have to say that some of the high school bands there were as good as any professional band I have heard. I was able to get a photo of the World War II memorial plaque you see in the tenth photo. That is quite the list consider just how small Murray State was during the period. The eleventh photo is a dedicatory plaque in honor of Mrs. Lovett. The final photo of the set is Sparks Hall. Sparks takes its name from Murray State’s sixth president, Harry M. Sparks. A native Kentuckian, Sparks began his career as a teacher, but had that role interrupted by World War II. He served in the Navy and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Commander. After the war, he returned to the states and completed his doctorate at the University of Kentucky. He joined the Murray State faculty in 1948 and by 1952 had become a department chair. In 1963, he became the Kentucky State Superintendent of Public Instruction. He returned as president in 1968 and continued in that position until his retirement in 1973. The building houses a variety of administrative offices and was completed in 1967 before Sparks returned to campus. I’m not sure when it was named after him. Murray State's athletics facilities are located on the northern end of campus. The first thing I came to on my walk was the softball field, which you can see in the first two photos below. As you can see from these photos, they were tending to the field the day of my visit. I played baseball for many years as in my youth and I still love to go to games to this day, and in my eyes one of the best sights of spring is a baseball or softball field being readied for a game. In the background of the second picture, you can see the CFSB Center, home of the Murray State basketball teams. The last photo of this set is a better view of the main entrance to the CFSB. The arena was originally named the Regional Special Events Center when it opened in the fall of 1998. The state of Kentucky provided $18 million (roughly $36.9 million in 2024 value) in funding for the arena with Murray State committing $2 million (just over $4 million in today’s value) for construction in 1995. Thanks to delays and cost overruns, the arena eventually came in with a $23 million price tag (about $44 million in today’s dollars). The 188,800 square feet facility seats 8,600, but it has an attendance record of 9,012 in a March 2, 2019, game with Austin Peay State University which Murray State won. Thanks to a naming rights contract of $3.3 million in 2010 (about $4.7 million today), the building was renamed for Community Financial Services Bank. It was the first arena in the Ohio Valley Conference to have jumbotron style video screens installed in 2009. Below we have the Roy Stewart Stadium, the home of the Murray State Racers football team. It is the second football stadium for the university. From 1934 until 1973, the Racers played in Cutchin Stadium, which was subsequently demolished. Its location is now a soccer field which sits behind the Curris Center. I don’t know if I was supposed to do so or not, but the stadium was open, and I simply walked in and went into the main set of stands. I could have walked out on the playing surface, but there were a couple of young men I presumed to be athletes running the perimeter of the field. I decided to not to press my luck and limited my experience to being in the stands. I found it interesting that the turf in Stewart is artificial. After all, there is an entire type of grass called Kentucky Bluegrass. I would have thought a natural playing surface of Kentucky Bluegrass would be the choice for Murray State, but such was not the case. The stadium can hold 16,800, but they have never sold out a game. Murray’s attendance record in Stewart 16,600, in a 1981 loss to Eastern Kentucky. By comparison, my alma mater Tennessee’s largest attendance at a game in Neyland Stadium was 109,061 in a 2004 game against Florida (Tennessee won). My other alma mater Texas Tech’s attendance record of 61,836 came in a loss to the Oklahoma State Cowboys in 2013. Forterra Stadium, the location of my soon-to-be alma mater Austin Peay State University’s football program has a record attendance of 12,201 which is a remarkable feat considering it technically only holds 10,000 people. That was achieved in a 2018 game when the Governor’s defeated Tennessee State University. Murray has not seen attendance meet or exceed 16,000 since 1981. The stadium is also technically a cemetery. Well, a pet cemetery. The first Racers mascot was a horse named Violet Cactus, who is buried inside the stadium. Violet Cactus was the only Murray mascot horse to carry that name; all the rest have been called Racer 1. The photos begin with a view of the stands from across the softball field. The gate was open, so I walked in thinking I would at least get a glimpse of the concessions part of the stadium, where I took the second photo. But, as I have noted, the place was completely open so I walked into the stands as can be seen in photos three, four, and five. The dedicatory plaque seen in the sixth photo is on the outside of the stadium. Across from the stadium is the memorial plaque seen in the seventh photo. It honors the passing of Murray native Gilbert Graves. Graves was the starting quarterback for Murray State who was seriously injured during a game at the then named West Tennessee Normal School (now the University of Memphis) on November 27, 1924. The 21-year old suffered a spinal cord injury. He was rushed to a local hospital where he was found to be paralyzed from the chin down. He died on December 5th. I didn't know it until serving on the dissertation committee of a former student athlete, but the main driver for the creation of the NCAA was the number of deaths and serious injuries which were rampant in college football in the early 20th Century. Despite the association being founded in 1906, such things were still all too common at the time of Graves' injury and death. Finally, this set closes with a bit of a blurry zoomed-in photo of the stands taken from the east on 12th street. I will close as I frequently do with photos of the Murray State lamppost sign. As I have noted on many occasions in this blog, lamppost signs are everywhere on college campuses these days. So much so that it is surprising when you come across a campus that does not have any. Murray State is no exception. In fact, they not only have loads of them, they have many different styles as well. The most common is the Murray State Shield in navy blue on a field of gold - the university's official colors. A good example of this can be seen in the first photo of this set which was taken just outside the Curris Center. They also have a number which highlight notable members of the Murray State community. The second photo shows one of these of John W. Carr just outside of the building which carries his name. Each of the residential colleges have their own shield and they dot the walkway to and from the residential portions of campus. There were also a few leftover centennial versions, one in navy, the other in gold, still hanging near the residence halls.