University Grounds

Menu

University grounds

|

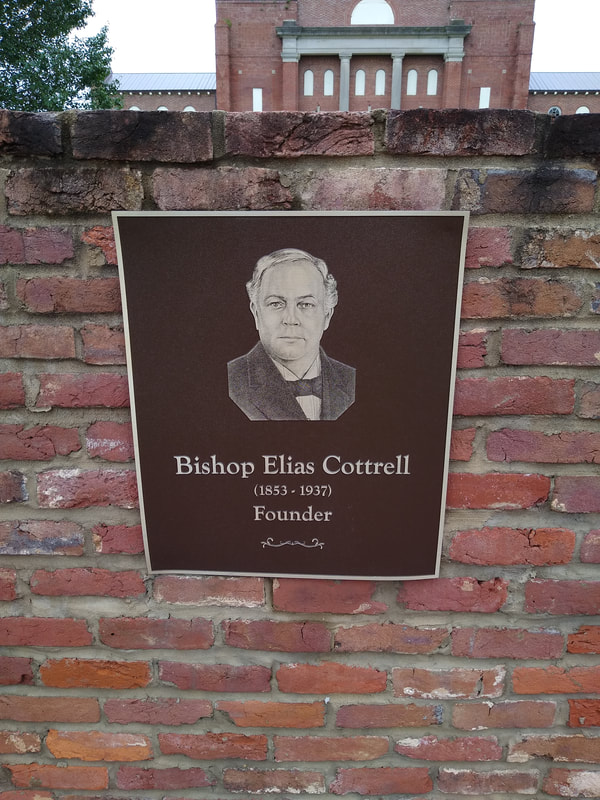

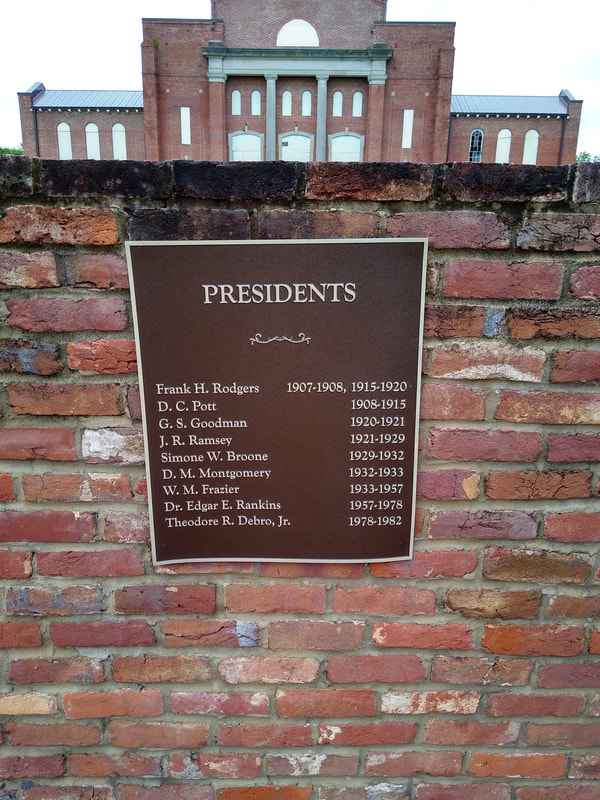

Today’s entry is another defunct institution. Unlike the only other one covered to date (the Memphis College of Art), this one has long been closed. The Mississippi Industrial College (MIC) was founded in 1905 by the Mississippi Conference of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. Bishop Elias Cottrell was the driving force and founder of the college. He had been working to open a school which would serve students at all levels (primary, secondary, and post-secondary) since the 1890’s. He established a board of trustees in 1900 and began the arduous process of fund raising. MIC opened its doors to students in January 1906. Some 200 students were enrolled that year. By 1908, enrollment grew to more than 450. The vast majority of students were not at the post-secondary level, however. Records indicate that most were primary school students. Still, the college was in existence and growing. The site in Holly Springs, MS, consisted of some 120 acres (donated in 1903) and were situated on Route 7, or Memphis Road as it was known (it is now referred to as Memphis Street). Apparently, the decision to name the school with “Industrial” in the title was two-fold. Although some industrial skills-type courses would be offered, the curriculum was more general at the lower levels and best described as a teacher’s college with a liberal arts tradition at the collegiate level. The Industrial moniker appealed to students and their parents who sought practical skills leading to employment and was a less controversial orientation to the white populace who did not feel that another liberal arts college was needed for African Americans in the region. You see, Rust College, another HBCU and a liberal arts college itself, was located directly across the street. Founded in 1866 by the United Methodist Church, Rust had been in existence for nearly fifty years when MIC opened its doors. Given the proximity of the two schools, one might wonder why MIC came into being. Unlike MIC, Rust was founded and funded by the white Methodist Church. It is named for Reverend Richard S. Rust, an antislavery activist from Cincinnati, OH. MIC, on the other hand, was funded by the African American Methodist Church, and its leadership and most of its faculty were not only black but were themselves educated at HBCU’s. Rust, with white supporters and many white faculty, was quite a different institution, and MIC was quite proud of its heritage. I will cover Rust in a future post. Upon its founding and for many years thereafter, students had daily chapel time and wore uniforms. The institution would carry on for 77 years. Unfortunately, desegregation had an unintended negative consequence for MIC. As was the case for some other HBCU’s, desegregation resulted in declining enrollment. African American students, now free to enroll in historically white institutions, chose to do so. Funding for the white schools had always been more robust and the school’s benefited from such wealth with more faculty, majors, and support services. The decline hit MIC hard. By the 1970’s enrollment drops were causing increasing financial hardships. In the early 1980’s, Rust College floated the idea of buying MIC, but the overture was dismissed by MIC. Federal funding cuts in 1981 led to the institution’s closing in 1982. The campus has been vacant since. A few years after its closing, the campus was acquired by Rust College who has maintained ownership of the site ever since. Despite much of the core campus being declared a historical site in 1980, it has largely been left to ruin. You can find photos on the internet of the campus over the last couple of decades showing the slow demise of the buildings. The day I visited this May began as a bright, sunny morning. But after my quick drive down from the Memphis area, clouds had rolled in, and it threatened rain. A gloomy feel and a damp silence permeated the air. It was, given the state of decay of the campus, both appropriate and eerie. Immediately after photographing the remains of the campus, I crossed the street to visit Rust College and within a half an hour on that campus the sun came out again. It was as if ghosts of MIC had arranged the gloom for my visit to add an air of grief at the state of the place. We begin with the college marker set in front of the Carnegie Auditorium Building. The sign is obviously a more recent addition, given that it notes the place as a historical site. Behind the college sign is the Carnegie Auditorium and Library. The Colonial Revival structure opened in 1923 and included a 2,000-seat auditorium and the college’s library. When it opened, it was the largest auditorium open to African Americans in the state. The roof has long since collapsed and vegetation covers part of the façade and even inside as well (at least in the areas where I could see in). Just this month, Rust College was awarded $500,000 from the National Park Service to restore the building. Obviously, $500k is not sufficient to bring such a large structure back to life in any usable form. I don’t know whether the goal is to raise additional funds or to simply use the existing amount to stabilize the building in a static form for reference. The building was designed by the Nashville-based architectural firm McKissack & McKissack. The firm was founded by Moses McKissack III in 1905 along with his brother Calvin. The McKissack’s have been architects since, with the family now operating a firm in Washington, DC. The building is a shaped as a “T” with the front entrance facing Memphis Street (looking east). Given the name and it use, in part, as a library, I am certain that at least half of the funds for its construction came from the Carnegie Foundation (which typically provided half of the funding for the buildings that carried the Carnegie name). However, scant information about the history of the building is available online (at least that I could easily find). The first photo is the front of the building, followed by two views of the north side of the structure. The last is south side. Immediately adjacent to the Carnegie Auditorium, to the north, sits Hammond Hall. Hammond was a residence hall for men and was designed in the Jacobean Revival style. It opened in 1907. I have been unable to find out for whom the building is named. It was designed by the Jackson, TN based architecture firm Heavener and McGhee. As you can see, the building’s residents have long since departed only to be replaced by ivy and a vulture sitting atop the front façade. Hammond can be seen in the first two photos. The building directly adjacent to Hammond to the north, seen in the second and third photos is Davis Hall, a gymnasium. I could not find any information about the building online. MIC had athletics for men, but not women, and were known as the Tigers. To the south of Carnegie is Washington Hall, which served as the administration building for the college and also contained classrooms. It was named for Booker T. Washington. The Colonial Revival building opened in 1910. The first photo below is north side of the structure. This is followed by three photos of the front of the building. The fourth and fifth are of the south side. The sixth is the rear of the building. Even the sidewalks are slowly giving way to nature. On the lawn in front of Washington Hall is what appears at first glance to be a headstone, seen here in the last photo of this series. It is, in reality, a tribute to William M. Frazier, MIC’s seventh president. His tenure at MIC was 29 years, with 24 of those as president. The marker was a gift of the MIC classes of 1955 and 1956. I am not sure when it was installed, but it was on the campus in the 1970's (see here). Just beyond Washington Hall is the now vacant spot where Cathrine Hall (that’s not a typo, there is no “e” after the “h” in the name) once stood. It was demolished in 2012. It was a beautiful building, and the first on campus. Opened in 1905, it was a three-story building with a large patio in front. It served as both a dorm for women and classrooms (although I believe later the classrooms were used for other purposes). Cathrine cost around $35,000 to build which is about $1.149 million in today's value. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and designated a Mississippi Landmark structure in in 2002. You can see photos of it in various states of decay online. The Mississippi Department of Archives and History has photos of it deteriorating away in 2011 as well as one color photo of it in June 1979 here. Behind Washington Hall were two small rectangular structures that were classroom buildings. I have seen old aerial photos of them. They look to have been rather nondescript buildings that were not named (at least I have found no records which have a name listed for them). One appears to be more or less gone - collapsed and covered with vegetation. The other, which sat closer to the rear of Washington Hall, is still visible. Seen here, it is basically a shell with the remains of the roof largely inside. Beside it is a sidewalk that apparently led to a service building of some sort (I have seen maps with a building outline but no name) but is now a path to nowhere. Old, abandoned buildings can be quite a sad site. To see an entire college left to ruin like this is heartbreaking. This is particularly so given the history of the college.

As I noted at the beginning of this post, you can find lots of photos of the campus since its closing online. Much fewer are photos of the campus when the college was operational and more limited yet is any substantive information about the place. If you would like to know more about the buildings, you can read the National Register of Historic Places application for the college site here. Also, Dr. Paul Batesel, a professor of English at Maryville State University in North Dakota, runs the blog America’s Lost Colleges. It is a wonderful blog and among all too many other closed colleges he’s covered he too has an entry on MIC which you can read here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AboutUniversity Grounds is a blog about college and university campuses, their buildings and grounds, and the people who live and work on them. Archives

February 2024

Australia

Victoria University of Melbourne Great Britain Glasgow College of Art University of Glasgow United States Alabama University of Alabama in Huntsville Arkansas Arkansas State University Mid-South California California State University, Fresno University of California, Irvine (1999) Colorado Illiff School of Theology University of Denver Indiana Indiana U Southeast Graduate Center Mississippi Blue Mountain College Millsaps College Mississippi Industrial College Mississippi State University Mississippi University for Women Northwest Mississippi CC Rust College University of Mississippi U of Mississippi Medical Center Missouri Barnes Jewish College Goldfarb SON Saint Louis University Montana Montana State University North Carolina NC State University Bell Tower University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Tennessee Baptist Health Sciences University College of Oak Ridge Freed-Hardeman University Jackson State Community College Lane College Memphis College of Art Rhodes College Southern College of Optometry Southwest Tennessee CC Union Ave Southwest Tennessee CC Macon Cove Union University University of Memphis University of Memphis Park Ave University of Memphis, Lambuth University of Tennessee HSC University of West Tennessee Texas Texas Tech University UTSA Downtown Utah University of Utah Westminster College Virginia Virginia Tech |