University Grounds

Menu

University grounds

|

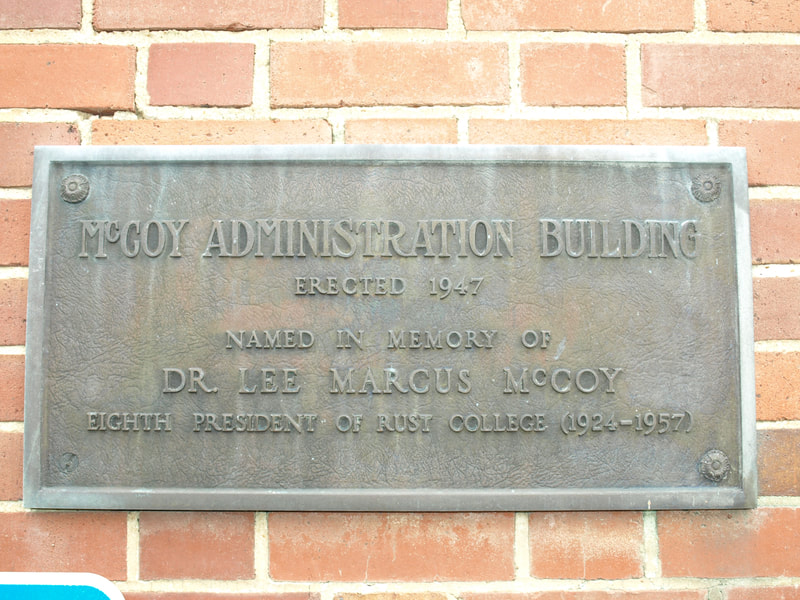

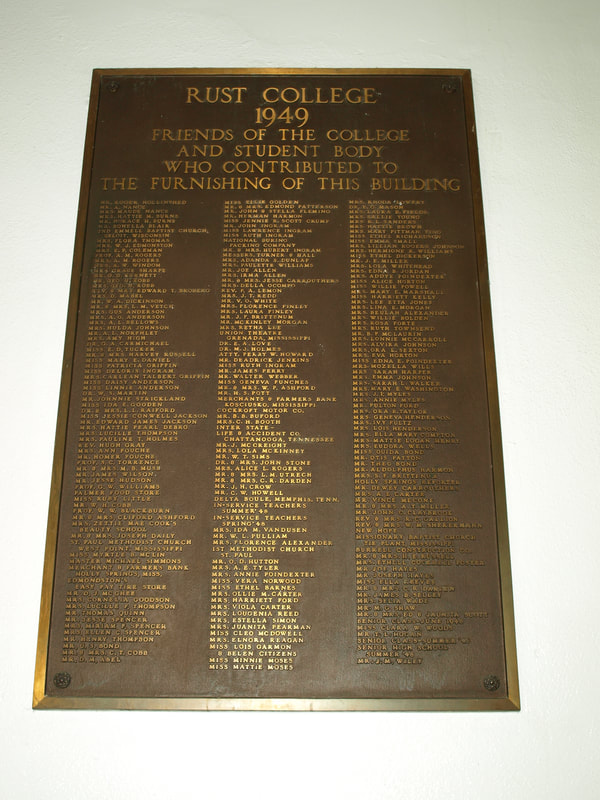

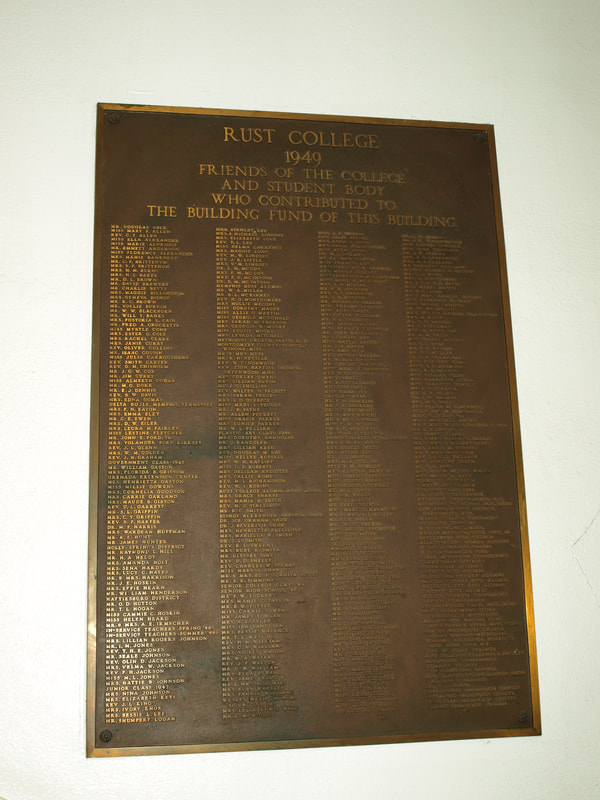

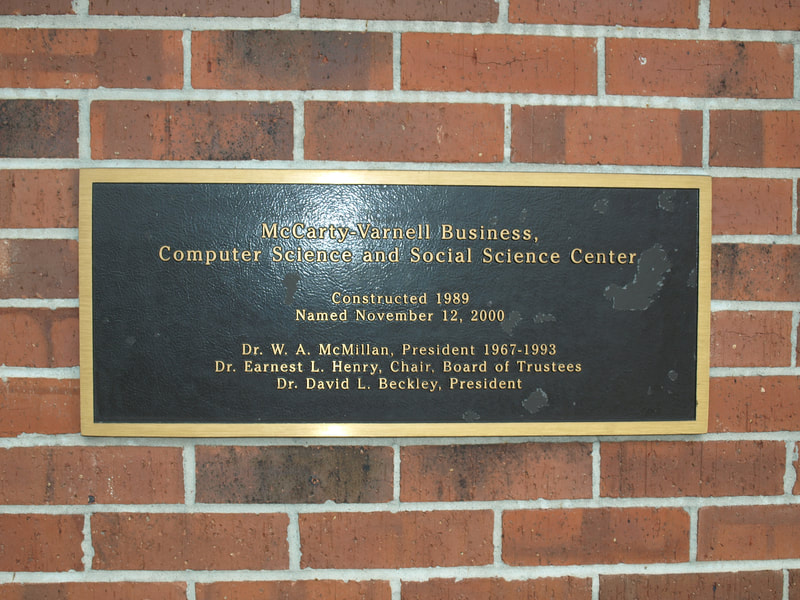

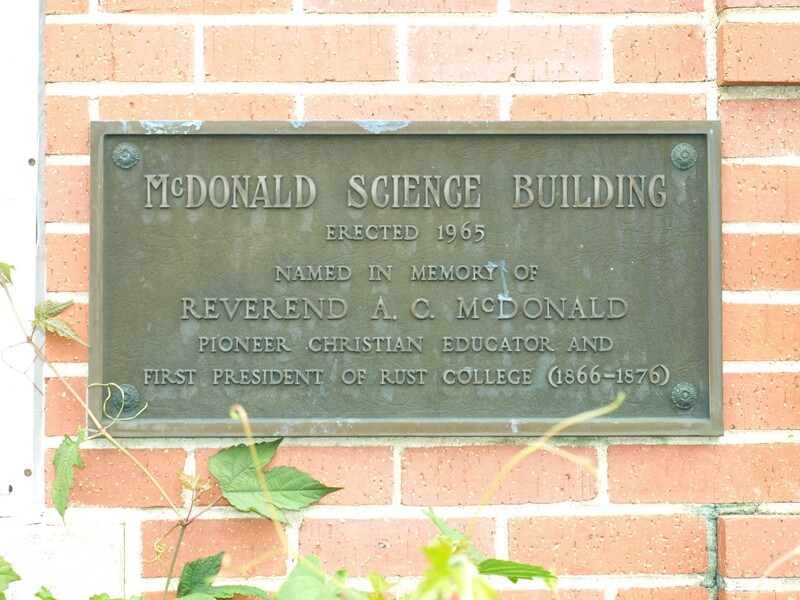

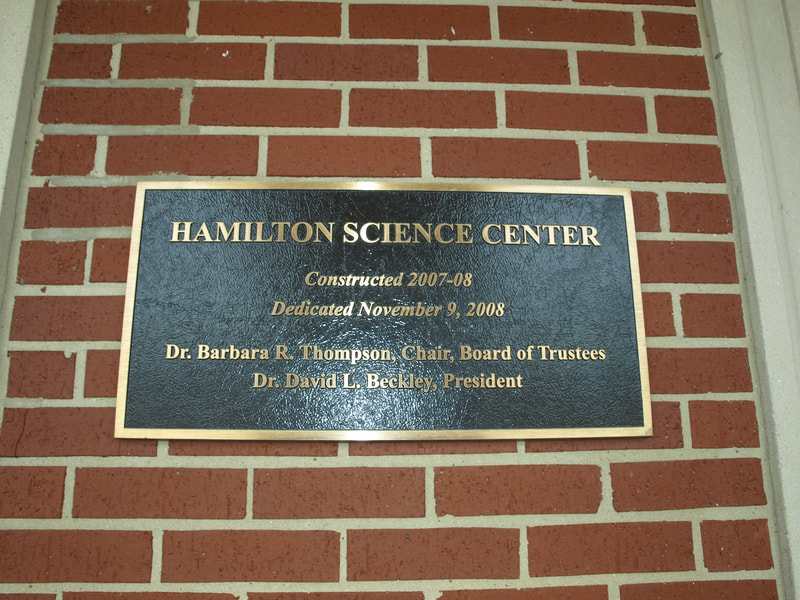

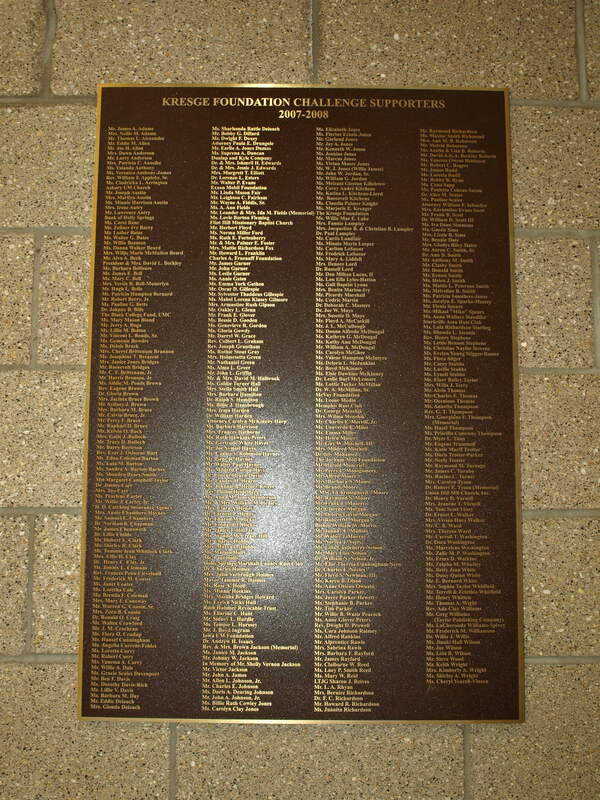

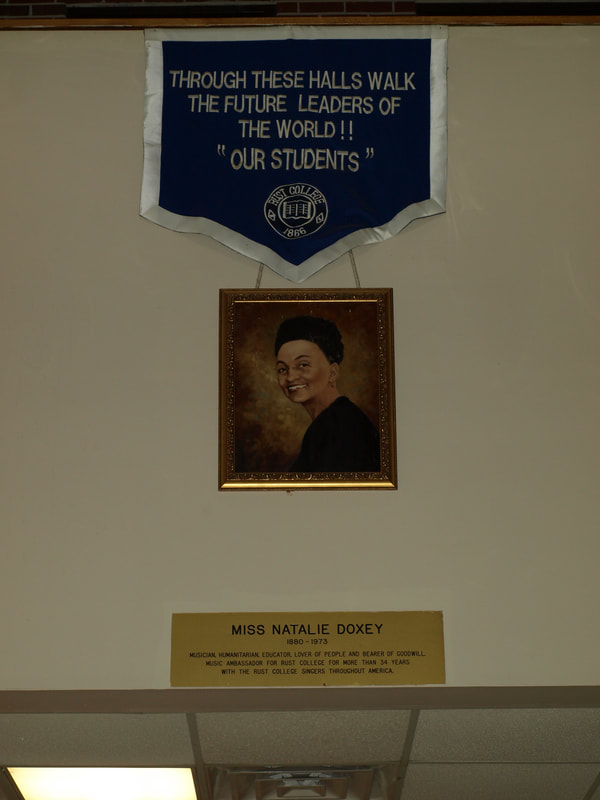

Today’s post is another HBCU that is close to my home in the Memphis area. Rust College is located in the small community of Holly Springs, MS, directly across the street from my last entry Mississippi Industrial College (MIC). I visited Rust the same day in late May that I visited MIC and although it was not the first time I was on the campus it was the first time I took photos. Rust College was founded by members of the Freedman’s Aid Society, a supported group of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and local African American preacher Moses Adams on November 24, 1866. The local leader of the Freedman’s Aid Society, Reverend Albert Collier McDonald began as the sole instructor and president, taught the first classes in the Ashbury Methodist Episcopal Church in Holly Springs. There was no name to the nascent institution at this point. It was meant to be a school at all levels (primary, secondary, and post-secondary) and most of its initial students were at the primary level. In 1868, the school was taken under the control of the Freedman’s Aid Society outright and a parcel of land at the current location was purchased for the construction of the institution’s first building. Not long after, ground was broken on what would become the first building which opened in 1869. The funding for the building was provided by Reverend S.O. Shaw who donated $10,000 (about $197,500 in 2022 value) for the purpose. The young institution would subsequently be named Shaw University in his honor. Sometime in the early years of the college’s existence, a local carpenter named James Madison Wells became a trustee of the university. Wells was a former slave who was the son of a slave owner; his mother Peggy was enslaved by his father. A local carpenter, Wells was the father of Ida B. Wells, noted journalist, educator, and Civil Rights advocate. Their home in Holly Springs is now the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum which is a few blocks from campus. Local reaction to the new institution were mixed. Some were against a school for African Americans but reports from the era note that a former local slave owner actively raised money for the college. The name, however, caused some confusion. The year prior to the founding of the college in Mississippi, another Shaw University was founded in Raleigh, North Carolina. That institution, named for Elijah Shaw, was (and is) an HBCU created in the same vein as the new Mississippi school. Thus, in 1892 the first name change occurred when the college was dubbed “Rust University” in honor of abolitionist Methodist Reverend Richard Rust. Richard S. Rust was born in Massachusetts on September 12, 1815. He attended Phillips Academy in Andover, MA, where he was introduced to anti-slavery ideas. Upon hearing a lecture by British abolitionist George Thompson, he formed an anti-slavery group on campus. He and his two fellow co-founders of the group were subsequently expelled for their activities. He went on to attend the integrated Noyes Academy in Canaan, New Hampshire. He attended Wesleyan University and upon graduation entered the ministry. He helped found the Freedman’s Aid Society which supported northern teachers who went south after the Civil War to teach former slaves. He was an avid supporter of educational opportunities for African Americans and was instrumental in the founding of Wilberforce University, an HBCU in Ohio, where he served as the first president from 1858–1862. Wilberforce is the oldest private HBCU. Rust’s two sons attended Wilberforce. You can read more about him here. The name would change again in 1914, this time owing the recognition that the small but growing school was not large nor comprehensive enough to carry the “university” moniker. The name became Rust College and it has remained so ever since. Still, pre-college instruction would continue. The elementary education program would cease in 1930; high school classes would continue until 1953. Rust sits on about 126 acres in Holly Springs, MS, just north of the historic downtown. Part of the site is a former plantation, and a good portion of the land was once the slave auction site for Holly Springs and the surrounding area. Today, nearly 1,000 students are enrolled in the school. First, we have the most notable building on campus – the McCoy Administration Building. The building is named in honor of Lee M. McCoy, the eighth president of the college (1924-1957) and the first alumnus (class of 1905) to lead the institution. McCoy was a native Mississippian, born in Tippah County on May 30, 1882. His 33-year tenure as president has to be among the longest of any college president. He was the youngest of nine children, all of whom were born after the Civil War. According to records from the Public Works Administration, his parents were former slaves, and their surname came from his father’s initial enslavers in South Carolina. His father became a preacher and despite not being able to read, he reportedly knew much of the Bible by memory. McCoy Hall was inspired by Independence Hall in Philadelphia and hence the striking resemblance. The two-story Colonial Revival Building is beautiful but did show its age in places on the exterior. That’s not terribly surprising given the age of the building and the common practice of deferred maintenance at virtually all colleges and universities. The tower is roughly seven stories tall. An addition was put in place in the rear of the building in 1972. The building came into being due to a tragedy. The college’s principal building had been Rust Hall, a large Romanesque structure that burned down on January 8, 1940. The loss impacted the college in both a practical and a spiritual sense. Rust Hall had been the campus centerpiece and was the location for the library, multiple classrooms, and even dorm rooms. The loss hit the campus community so hard that many felt the college should relocate. Some advocated a move to Jackson, MS, others to the closer community of Memphis. McCoy was determined to see the college stay in Holly Springs and worked diligently to raise funds to construct a new building. The timing of the fire at time when the effects of the Great Depression were still ever present and at the beginning of the American involvement in World War II made the process all the more difficult. Classroom space was at such a premium that for years classes were held in the president’s house. The building opened in 1947 having been built at a cost of roughly $300,000 (or about $4.5 million in 2022 value). A great proportion of the funds came from donations from the CME Churches of the state and region; about $60,000 came from white Methodist Churches with much of those funds collected on donations on “Race Relations Sundays”. The 1947-1948 academic year saw the college have 327 students. The photos below begin with four views of the front façade looking north. The historical plate seen in the sixth photo is just to the left of the main entrance; the corner stone with the “Administration Building” inscription is just to the right of the main doors. The seventh photo is the vestibule just inside the main doorway. The nineth and tenth photos are plaques inside this area from 1949 noting donors who helped make the building possible. The banner noting the sesquicentennial (in 2016), was standing adjacent to the doorway. The last photo is an entrance on the west side of the structure (looking eastward). The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998. Next, we have the Leontyne Price Library. The library is named in honor of notable soprano Mary Violet Leontyne Price, the first African American to be a leading performer at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Ms. Price was born and raised in Mississippi, in the community of Laurel in the southern part of the state. Her mother attended Rust, although I do not believe she graduated. This association led her to be a vocal and active supporter of the college. She gave a concert in Jackson, MS, in March 1967 which raised $34,000 (nearly $300,000 in 2022) to support Rust. She was also served as National Co-Chair of the Rust College Capital Campaign in 1967/1968. She personally endowed a scholarship at Rust. The library sits behind (to the north) of McCoy Hall in the heart of the campus. The building opened in 1970 and comes in at 30,440 square feet of space. The library was designed by local Memphis firm Gassner/Nathan/Browne Architects and Planners. The group designed many iconic buildings throughout the region including structures at Lemoyne-Owen College and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. Firm co-founder Thomas Nathan singled out Price along with a library at Lemoyne-Owen and a student housing building at Vanderbilt as his favorites. Sometime last year, I bought a copy of the book "Campus Buildings That Work", a 1972 piece edited by Linda Boring El-Shishini. The Leontyne Price Library has two pages of photos dedicated to it in the book. I had first read the book as an undergraduate at the University of Tennessee more than thirty years ago. As an aside, the collection of books on universities and collegiate architecture at UT is quite large if you are interested in such things and find yourself in Knoxville. The book is very representative of the times in two ways. First, it highlights collegiate structures built in the years just prior to publication. Second, it is very enthusiastic about the architecture of that time. So much so that I believe a more honest title would be "In Praise of Brutalism". Still, it is a good book that has wonderful photos of buildings of that era including several of the Price Library shortly after it opened. The photos below begin with three views of the front of the building (looking north). The fourth photo is a stairway just inside the front door. The main stacks are on the second floor just up these stairs. The first floor has a small gallery with some very interesting African and African American art as seen in the last photo. I did not have time to fully explore the building and did not go to the third floor, but I believe it houses offices and stacks. Next, we have the McCarty-Varnell Business, Computer Science, and Social Science Center. The McCarty portion of the name comes from a major donor to the college, Hyman Folk “Mac” McCarty Jr. McCarty transformed his father’s single feed and seed store operation into one of the biggest poultry businesses in the nation. McCarty was a notable philanthropist, giving funds to colleges and universities across the state, particularly to his alma mater the University of Mississippi. In addition, he gave funds to establish professorships at Jackson State University and Millsaps College. The Varnell name is in honor of Jeanne Thompson Varnell, part of the Hyde family of Memphis who created the AutoZone retail chain (and for whom a building is named at Rhodes College in Memphis). She was a long serving member of the Rust College Board of Trustees. She was also a member and the first female chair of the Board of Trustees of Lambuth University. The first photo is the front of the building which faces southwest. The plaque in the second photo is by the front doors. The last three photos are interior shots of the first-floor hallway and a large lecture hall near the main entrance (photos three, four, and five respectively. Next we have three buildings which are all connected to one another. The original structure of the three is the McDonald Science Building. Two additions to the structure were added over the years including the Emma B. Miller Annex (which as the name implies is really an addition and not a true attached building) and the Hamilton Science Center. The McDonald portion of the building opened in 1965 and is one of three buildings erected during the presidency of Earnest A. Smith. The Science Building is not the first structure on the Rust campus to carry the McDonald name. According to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, there was a McDonald Hall on campus which opened in 1869 (according to information available on the Atlanta Journal Constitution website, construction began in 1867). I don’t know what became of that original structure. The name, of course, is in honor of Rust’s first president, Reverend Albert Collier McDonald. There was no plaque for the Miller Annex and I have been unable to find any information about the name or the addition online. The Hamilton Science Center is obviously the newer part of the complex. The building is named in honor of Dr. Ralph and Barbara Hamilton, who gave funds to support the construction of the building. Dr. Hamilton was a noted ophthalmologist here in Memphis. An alumnus of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC: class of 1952), he went on to be on faculty there. He was born in Knoxville, TN, and did his undergraduate work at UT Knoxville (class of 1950). I believe he met his wife while attending UTHSC although I cannot confirm that at this point. Mrs. Hamilton, a graduate of Rhodes, is, I believe, a native to West Tennessee. The Hamilton’s were significant philanthropists to causes in Memphis and the Mid-South. The UTHSC Hamilton Eye Center was created in part by one of their donations. Among their many contributions is the Hamilton Endowed Professorship in Ophthalmology at UTHSC. There is also a scholarship named for the Hamilton’s at Rust. In addition to the funds from the Hamilton’s, Rust received $1.5M grant from the Kresge Foundation to support the construction of the building at to do some remodeling McDonald building. The building was dedicated in a ceremony on November 9, 2008. Among the dignitaries present was former Mississippi Governor William F. Winter. The photos below begin with a shot of the main entrance to McDonald on the south side of the building. The dedication plaque in the second photo is just to the right of the main entrance. The third photo shows McDonald and the Miller Annex when looking northward. The annex can be discerned by the exposed gutters, as well as different windows and trim work at the top as compared to McDonald. The fourth photo is the main entrance to the annex which is on the east side of the structure. The remaining photos are of the Hamilton Science Center. The front of the building is to the north of McDonald. There are numerous residence halls on campus, and I had the opportunity to photograph three of them on my visit. These include Wiff Hall, Gross Hall, and Davage-Smith Hall. The 1st photo below is Wiff Hall. The building was, obviously, undergoing a significant renovation during my visit. In addition to work on the inside of the building I could see that brickwork on the front façade had been repointed. Wiff opened in 1965, the building historically had space for 96 students. Many colleges expand individual student space when renovating old dorms and that will be the case with Wiff Hall. The dorm was previously only for women, but it will be coed after the renovation. Wiff is one of three buildings constructed during the presidency of Earnest A. Smith, Rust’s ninth president (the other two being Gross Hall and the McDonald Science Center). I was unable to find out for whom the building is named. The second and third photos are of the front Gross Hall which, like Wiff, opened in 1965. Since it opened, Gross has been a dorm for men. The building is scheduled for a remodel to begin sometime in the next year or so. Unlike the Wiff Hall renovation, the floorplan of Gross is not changing. I was unable to find out anything about the name of the building. The set concludes with a photo of Davage-Smith Hall. The first part of the building’s name is in honor of Matthew S. Davage, who became the first African American to be president of Rust in 1920 (his term in office was from 1920 to 1924). Davage was a native of Louisiana, having been born in Shreveport on June 16, 1879. He served as president of five colleges during his lifetime. These included George R. Smith College (Missouri), the Haven Institute (Mississippi), Samuel Huston College (Texas), and Clark University (Georgia). In addition to these (and Rust obviously), he was interim president of the combined Huston-Tillotson College. He also served on the board of trustees of eight colleges, and from 1940 until 1952 he was Director for all African American colleges and universities for the Department of Higher Education of the Methodist Board of Education. The second part of the name is in honor of Earnest A. Smith, Rust’s ninth president. Next, we have the Doxey Alumni Fine Arts Communications Center. The building is named in honor of Ms. Natalie Doxey, a Rust alumnae who would stay at the college for most of her career. She founded the Rust “A 'Cappella Choir” in 1930 and the group would remain well known through her tenure there. In addition to routine concerts and tours, under her direction the group would often tour to raise funds for the college. She stayed with Rust as a music instructor and director of the choir until her retirement in 1969. Ms. Doxey was born in 1880. She passed in 1973, a year before the building which now carries her name was opened. The set below begins with two views of the front (west side) of the building. The third photo is a portrait of Ms. Doxey which hangs just inside the vestibule which can be seen more fully in the last photo. The first photo below is the James A. Elam Chapel. It is, of course, named for James Elam. Elam founded Belmonte Park Laboratories in Ohio and used the wealth this venture afforded him to be a philanthropist for many causes. He was a significant contributor to his alma mater, Central State University. He was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree from Rust in April 2000. The chapel was completed in 2001. The chapel sits near the main campus entrance on the south side of the grounds. The second photo is the R.A. and Ruth M. Brown Mass Communications Center. The building is named in honor of Rainsford A. Brown and his wife Ruth of Iowa. Mr. Brown was active in the Methodist Church and became a trustee of Rust College as well as for the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary and Cornell College. There is also a scholarship, the Rainsford A. and Ruth M. Brown Award at Rust. The building sits just southeast of McCoy Hall. Lastly, we have the W.A. McMillan Multipurpose Center and Kinzell Lawson Gymnasium. Dr. William Asbury McMillan was the 10th president of Rust, a position he held for twenty-six years. He had previously been a dean there. McMillan was a native of North Carolina. He completed his undergraduate studies at Johnson C. Smith University and his master’s and Ph.D. at the University of Michigan. Rust also has a scholarship in his name. Kinzell Lawson was a longtime fixture in Rust athletics. He coached basketball, track, and when they had it, football (Rust ceased having a football team in 1965). He passed away in December 2000 at the age of 91. The first two photos are the front of the building and the third was taken just inside the front doors.

1 Comment

Zupuriuh Harrington

1/24/2024 02:50:57 pm

Great information!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AboutUniversity Grounds is a blog about college and university campuses, their buildings and grounds, and the people who live and work on them. Archives

February 2024

Australia

Victoria University of Melbourne Great Britain Glasgow College of Art University of Glasgow United States Alabama University of Alabama in Huntsville Arkansas Arkansas State University Mid-South California California State University, Fresno University of California, Irvine (1999) Colorado Illiff School of Theology University of Denver Indiana Indiana U Southeast Graduate Center Mississippi Blue Mountain College Millsaps College Mississippi Industrial College Mississippi State University Mississippi University for Women Northwest Mississippi CC Rust College University of Mississippi U of Mississippi Medical Center Missouri Barnes Jewish College Goldfarb SON Saint Louis University Montana Montana State University North Carolina NC State University Bell Tower University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Tennessee Baptist Health Sciences University College of Oak Ridge Freed-Hardeman University Jackson State Community College Lane College Memphis College of Art Rhodes College Southern College of Optometry Southwest Tennessee CC Union Ave Southwest Tennessee CC Macon Cove Union University University of Memphis University of Memphis Park Ave University of Memphis, Lambuth University of Tennessee HSC University of West Tennessee Texas Texas Tech University UTSA Downtown Utah University of Utah Westminster College Virginia Virginia Tech |