University Grounds

Menu

University grounds

|

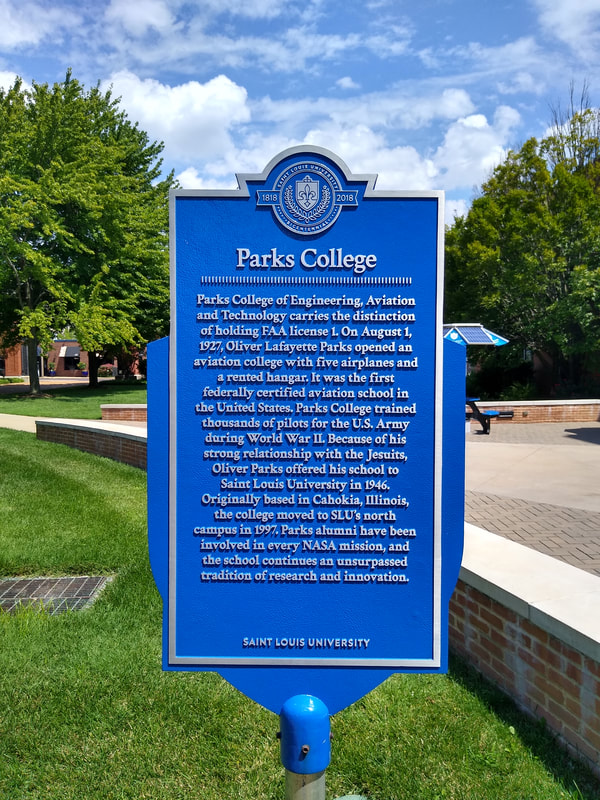

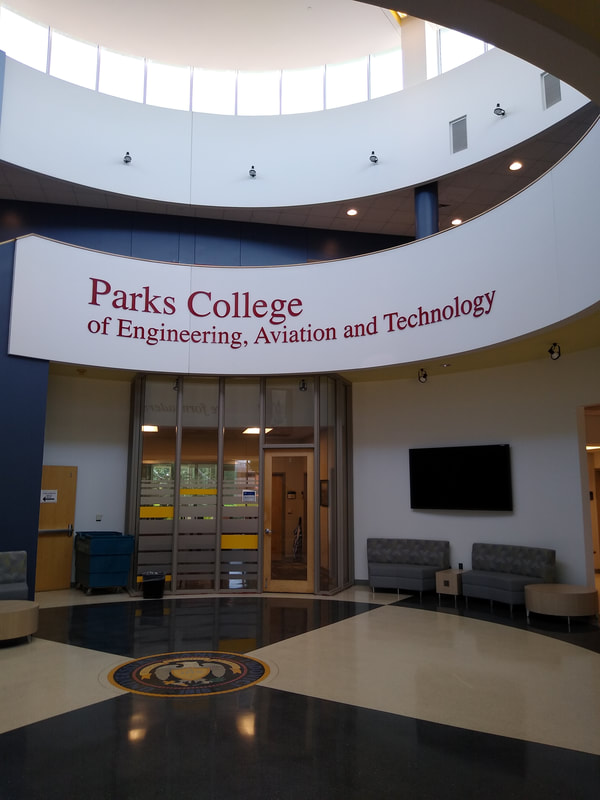

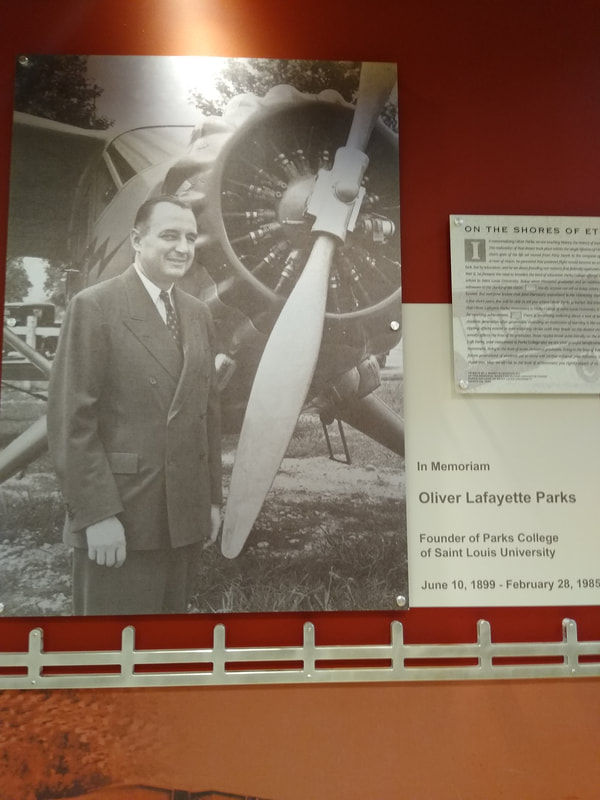

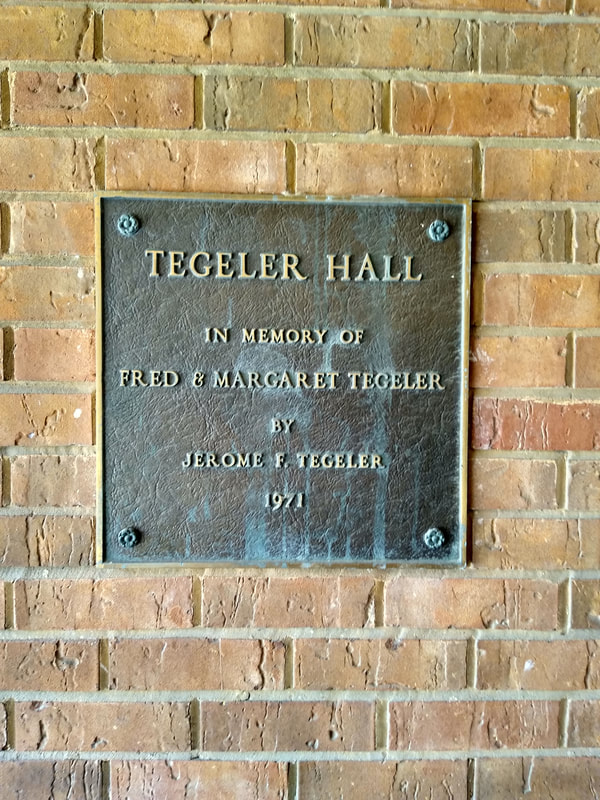

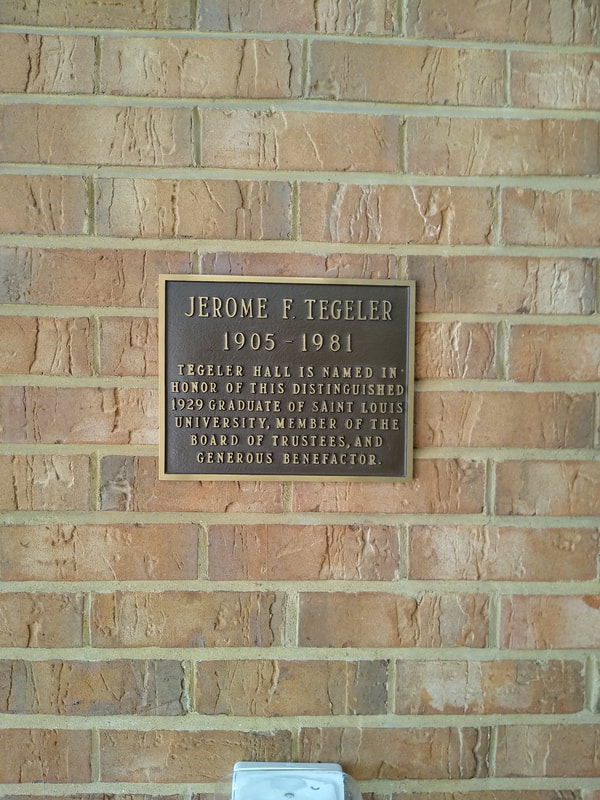

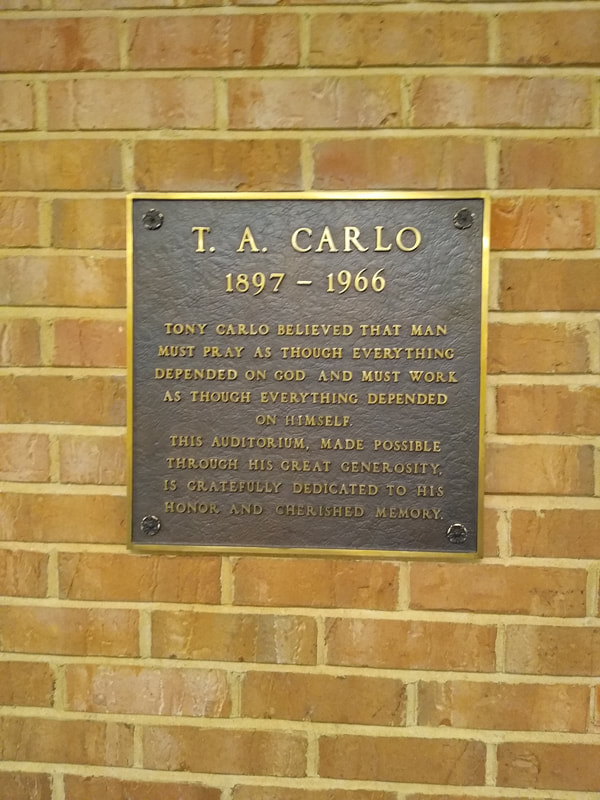

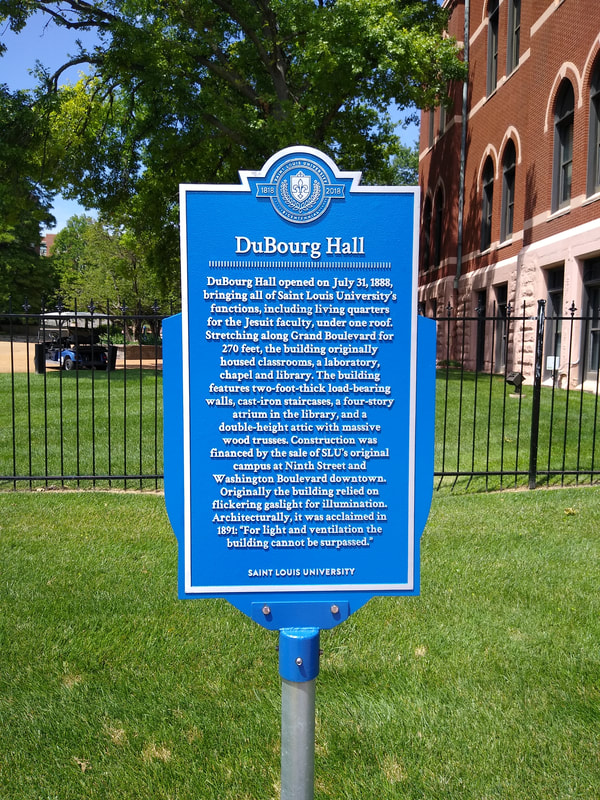

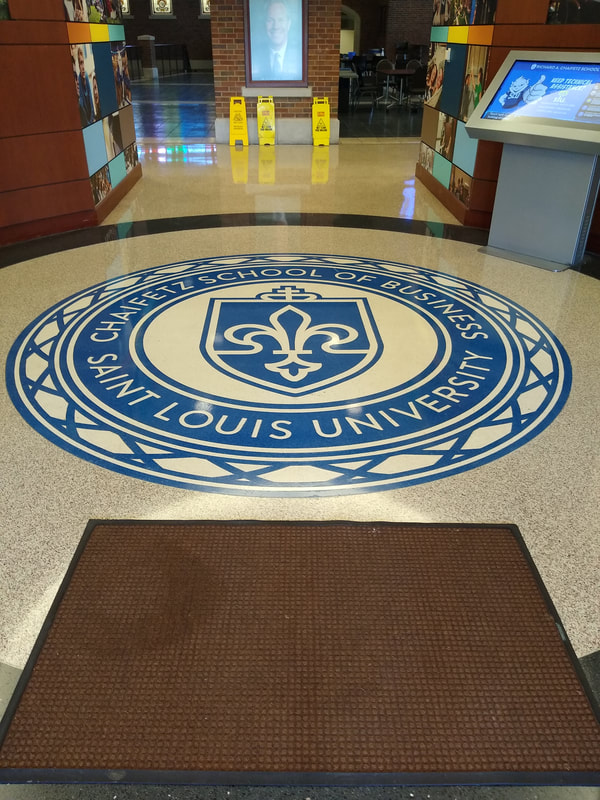

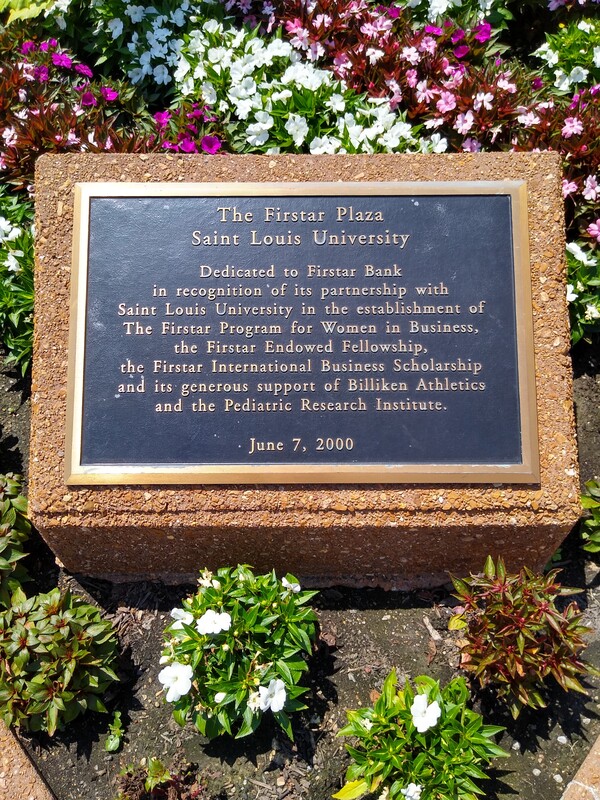

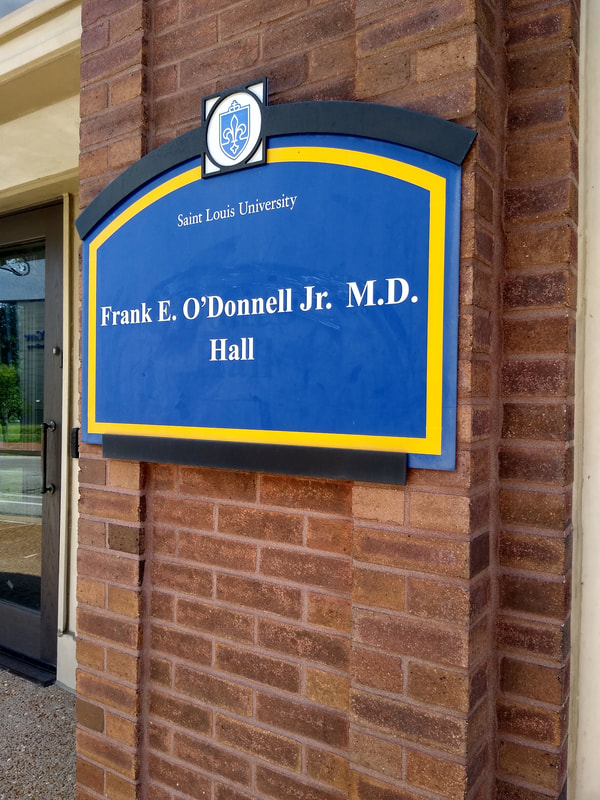

I was back in St. Louis the first weekend of this month for a board meeting. The metropolitan area is home to 30 colleges and universities. When I was there in March of this year, I only had time to take one snapshot of the Barnes Jewish College Goldfarb School of Nursing and I really wanted to be able to visit at least two or three campuses during this visit. As fate would have it, I was too busy to do much exploring, plus it was incredibly hot and humid during my visit. Time allowed me the opportunity to visit both the North and South campuses of Saint Louis University, and perhaps another college in the area, but the summer swelter was so bad I was only able visit the two SLU campuses. If you have driven through St. Louis on I-64, you have no doubt seen SLU from the freeway. The Chaifetz Arena and several large dorm towers on campus are easily seen from the Interstate. These large, modern structures do not represent the bulk of campus, however, which is dotted with a variety of old and new buildings many with significant charm and architectural splendor. Despite its urban location and proximity to downtown, it also has some lovely greenspaces which give the inner campus a traditional collegiate feel. The campus was relatively quiet during my visit. It was the time between the summer and fall semesters and few students were on campus. There were, however, some incoming students and their families on campus. I did have the chance to chat with a few students, faculty, and staff during my visit and they were all very nice and welcoming. I imagine the place is buzzing during the academic year. I would recommend a visit if you happen to be in the city and have some time on your hands. After my visit, I purchased the book Saint Louis University: A Concise History by William Barnaby Faherty, S.J., in preparation for this post thinking it would have information on the various buildings on campus. Although it is a good book on the overall history of the university and a very quick read (it's only 74 pages), it does not have much in the way of the history of the campus architecture. I was also able to get my hands on a copy of the book Saint Louis University: 125 Years by Rita G. Adams, William C. Einspanier, and B.T. Lukaszewski, S.J. (SLU folks fondly called him Father Luke) through the interlibrary loan service here at the University of Memphis. It was a great resource for photos and some background but still not as in-depth as I would have liked. That means that in some cases I cannot give too many details on the buildings you will see. This is particularly true for the structures on the South (health sciences) campus. Although the university has some good background information and a host of historical photos online for the North Campus, it has only a sparse collection for the South Campus. If you happen to know of a source of good information on SLU’s architecture, please leave a comment. Since its founding just over two centuries ago, the university has accomplished much, many of which were firsts. When it was founded as Saint Louis Academy in 1818, it was the first post-secondary institution west of the Mississippi River. It quickly grew to be Saint Louis College and then, in 1832, Saint Louis University. The change to university status by means of a new state charter made SLU the first university west of the Mississippi. In 1836, the university established a School of Medicine, again the first west of the river. The law school, established in 1843, was also the first west of the Mississippi. The first forward pass in football was made by Bradbury Robinson in 1906. The first geophysics department in the Western Hemisphere was established by Professor James B. Macelwane, S.J., in 1925. Although not part of SLU when it was established, the Parks Air College, now the Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology, was the established in 1927. It is the oldest Federally Certified school of aviation west of the Mississippi. SLU integrated in 1944; the first college in the former Confederate States to do so. There are many other firsts – the first school of public health in Missouri and the first university in Missouri to offer a Ph.D. in nursing among them. Doctors at the Saint Louis University Hospital completed the first heart transplant in the Midwest in 1972. The list is notable not merely for the accomplishments but for the sheer number of them as well. SLU held its first classes on November 16, 1818, in a small building rented from Madame Eugene Alvarez. Then known as the Saint Louis Academy, students were all boys and young men. The next year, fundraising began for a new building. By 1820 the new building, a two-story brick structure was opened, and the fledgling institution had a new name – Saint Louis College. At the request of Bishop DuBourg, a group of Jesuits came to Saint Louis in 1826 and work began to expand the school. On November 2, 1829, a new building opened on land donated by St. Louis resident Jeremiah Connor between 9th and 10th street. The campus would slowly grow on this site. The 1829 building (which Adams, Einspanier, and Lukaszewski indicates closed in 1833, but I am not sure why) was joined by a medical school building and a philosophy building in 1836, and by a classroom building in 1853. The entire campus was surrounded by a nine-foot-high wall in 1838. The city of St. Louis would continue to grow and as it did the campus began to be crowded by businesses. The impact of the city’s growth was two-fold. In the immediate sense, the possibility for expanding the campus became less as the city grew around it. At the same time, many of the surrounding businesses were bars and other concerns that the Jesuits found unappealing. As they looked for space to grow, the considered locations that had available space and a less urban environment. The university acquired the first element of the current campus, a few miles from the existing downtown space, in 1867. The university reminds me of Virginia Commonwealth University in a number of ways. Although it is much smaller than VCU, its location in the urban core of St. Louis is reminiscent of VCU. Both institutions also have a health sciences campus that is a couple of miles away from the traditional campus. In VCU’s case, the two campuses are a result of the school being merged from two existing institutions. In SLU’s case, I believe the location difference was a matter of availability of land. In SLU’s case, the two campuses are about a mile apart, at least as the crow flies between their two closest points. SLU’s campuses carry a simple moniker related to their relative position: the North Campus is the location for the traditional academic programs; the South Campus houses the health sciences. For a time, the North Campus was known as the Frost Campus. The name Frost comes from General Daniel Frost, a native of New York and an alumnus of the United States Military Academy (West Point). Frost would first go to Missouri when stationed at the Jefferson Barracks in Saint Louis in 1850 (the location of the Barracks is actually now part of the North Campus). He resigned from the Army in 1853 and became part owner of a lumber mill company. He was elected to the Missouri legislature in 1854 and during this time served as a member of the West Point Board of Visitors. A proponent of slavery, he actively worked to get the practice established in Kansas. He helped establish the Confederate-leaning Minutemen organization and subsequently joined the Confederate Army. In 1959, his daughter Harriett Frost Fordyce donated $1 million (about $9.9 million in 2022 value) to the university for the purchase of 22 acres of land that are now part of campus. The campus was subsequently named in his honor. As recently as 2017, official publications still found in the corners of the web have the name listed as the Frost Campus. I am not certain when it was changed to its current moniker of simply the “North Campus” but given the namesake’s background it is not surprising that the change occurred. The North Campus is directly beside the campus of Harris-Stowe State University, and I wanted to continue my tour onto that campus. The heat and humidity of the day at first deterred me, but the idea was moot when I realized the time and I had to be on my way. I imagine I will be back in the city at some point, if for no other reason than to tour the other numerous college campuses in the area for this blog. The university has numerous gates that mark the entrances to campus. Most consist of two brick columns with a metal archway with the university seal and name. We begin with a photo of two such gateways, standing on opposite sides of South Grand Avenue which bisects the North Campus. This virtual tour of campus will be ordered in the way I saw it the day of my visit. I parked on Lindell Boulevard just east of Grand Avenue and entered campus through a gate near McDonnell Douglas Hall. McDonnell Douglas was dedicated in a ceremony on September 27, 1997. John F. McDonnell, the former chairman and CEO of McDonnell Douglas and the son of McDonnell Aircraft founder John S. McDonnell was at the ceremony. Until its merger with Boeing in 1997, McDonnell Douglas' corporate headquarters were located at the St. Louis International Airport. The building comes in at about 90,000 square feet of space and houses classrooms, offices, conference rooms, and a 300-seat auditorium. The site was formerly the home to a hotel that had become dilapidated and “seedy” according to observers at the time. The building, and the Parks' College presence on the North Campus is relatively new. McDonnell Douglas is the home to the Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology. As noted above, Parks began its life as a separate institution, having been founded in 1927 as a school to train pilots. It was the first federally certified school of aviation in the U.S. It takes its name from the founder of the school, Oliver Parks. Parks was working as a car salesman when he learned to fly in 1926. He became a friend of Charles Lindburgh and within a year of gaining his pilot's license, the college was established. Parks was a crucial source of pilots during World War II. The Parks College campus was in Cahokia, Illinois, literally just across the Mississippi River from downtown St. Louis. Mr. Parks gave the college to SLU, including all buildings and land, on August 1, 1946. The value of the totality of the gift was estimated to be about $3 million (or just over $45 million in today's value). Parks would stay on as dean for three years, accepting a salary of only $1 per year for his efforts. Parks would also serve as chairman of the expansion fund drive for SLU during this time. Not only would college remain on its campus in Cahokia, but additional facilities were also built in the coming years. I believe the campus officially closed with the opening of McDonnell Douglas Hall. SLU donated the campus and buildings to the town of Cahokia. A notable alumnus of Park was Gene Kranz who was Chief Flight Director at NASA during the Gemini and Apollo missions. He was famous for his mission vests made for him by his wife Marta. He was portrayed by Ed Harris in the movie Apollo 13. The first seven photos are views of the south side of the buildings and the courtyard on the south and west ends of the building. The courtyard features tables with solar powered charging spots, similar to those I saw at the Southwest Tennessee Community College Union Avenue campus. Just inside the main entrance is a large rotunda area (photos eight and nine) which features a dome and a terrazzo floor complete with the university's seal (photo ten). The eleventh photo is a painting of Oliver Parks seen in the rotunda area. A statue of astronaut John “Jack” Leonard Swigert, Jr. stands in the rotunda on the main floor as seen here in the twelfth photo as well. Swigert was a last-minute addition to the crew of Apollo 13, having joined the crew two days prior to launch. He was portrayed in the eponymous movie by Kevin Bacon. I could not find any connection between him and SLU. He is a native of Colorado and a graduate of the University of Colorado, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and the University of Hartford. I suppose the connection is via McDonnell and their work on the space program. None the less, it is a fitting tribute to a great American. Along the inside south wall of the building is a mural that depicts the history of the Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology, partially seen here in photos thirteen and fourteen. The banner seen in the fifteenth photo is on an adjoining wall at the end of the mural. It depicts the SLU mascot the Billiken as an engineer. Being an aviation school, it is not surprising that the college has its own flight simulator (photo sixteen). There are several alcoves that line the inside ring of the second floor of the building, and each has a piece of art. Here you can see two examples in photos seventeen and eighteen. The last photo was taken from beside McDonnell Douglas looking southward. It shows a statue of Charles Lindburgh. Behind the stature you can see part of Oliver Hall. Although I am not certain, I believe Oliver Hall was named after Oliver Parks. It is used as an engineering lab space. It started life as the SLU Central Utilities Plant as can be seen here and here. Just to the southeast of McDonnell Douglas is the SLU Soccer Field. If you are a soccer buff, you probably know that SLU has one of the most historic programs in collegiate athletics. The Men’s soccer team holds the record for consecutive appearances in the Division I Championship Tournament and won a staggering 10 National Championships during the 15-year period from 1959 to 1973! During this time, they made six consecutive appearances in the National Championship games. It was an era for dynasties as it was during this time that the UCLA Bruins won 10 national titles in men’s basketball under coach John Wooden. Football came to SLU in 1888 in a game against a squad from nearby Washington University. True intercollegiate play would commence in 1899 and would continue until 1949, although no games were played in 1943 or 1944 due to World War II. Football would come back as a club sport in 1968, but that would be discontinued after the 1973 season. Still, the football program had one notable accomplishment. Although Walter Camp of Yale threw the first forward pass in 1876, the play was illegal by the rules of the game at that time. History tells us that the first “legal” forward pass came in a 1905 contest between Washburn University and Wichita State University (then known as Fairmont College). In that game, which was considered experimental due to it allowing the forward pass as a test as well as the then new idea of requiring ten-yard advancements to achieve first downs, Bill Davis connected with Art Solter. Many consider this to the be the first legal first pass, and in a way it was. But there nothing normal about the game in terms of scheduling and rules. That particular game was held on Christmas Day 1905. The rules allowing for the forward pass would not actually be in effect until the 1906 season. On September 5, 1906, SLU travelled to Wisconsin to play Carroll College. During the game, Bradbury Robinson completed a throw to Jack Schneider making the SLU the first to complete a legal forward pass in regular play. Behind the Soccer Field you can see the Chaifetz Arena in the distance. I had intended to get over there and take a look around, but the heat was punishing, and I eventually opted out of the walk over there. Chaifetz officially opened on April 10, 2008 and came in at a total cost of $80.5 million (or about $109 million today). Chaifetz is named after alumnus Dr. Richard Chaifetz (Class of 1975) who donated $12 million for the construction of the facility. Chaifetz is a psychologist by training who founded the ComPsych Corporation and the Chaifetz Group. He was a freshman at SLU when his estranged father stopped paying his tuition. He asked for help from the president of SLU, Reverend Paul C. Reinert, S.J., telling him that if he could stay he would later repay his tuition and much more. He more than lived up to that promise. Chaifetz and his wife Jill would later donate an additional $15 million to the university which subsequently named the business school after him (see below). Chaifetz seats up to 10,600 in its main arena, 1,000 in a practice facility, and has work out space, locker rooms, and other amenities. The last two photos are the Mark Werle Memorial Plaza and fountain. Werle was an undergraduate at SLU when he passed. Next, we have Fitzgerald Hall, seen in the first two photos of the set below. The building was named in honor of Thomas Fitzgerald, S.J., the 30th President of SLU. He served in that role from 1979 to 1987 and was notable in leading the university from a deficit state to a robust financial status. The university’s endowment grew nearly two and a half times during his tenure, increasing from $57 to $141 million. He was instrumental in the development of campus as well. A new law school building opened during his tenure, the library was expanded, the Simon Recreational Center was built, and a major expansion and renovation of the Saint Louis University Hospital (see below) was completed as well. One of the best things he accomplished architecturally during his presidency was transitioning Pine Street, which formally cut through the heart of campus, into a pedestrian mall. This undoubtedly changed not only the appearance of the campus, but also gave it the serene center it now enjoys. Fitzgerald had previously served as President of Fairfield University in Connecticut from 1973 until 1977 when he came to SLU. Fitzgerald Hall is the home of the SLU School of Education, and I believe it opened with that role. In trying to learn more about the building, I discovered that Fitzgerald Hall is an extremely common name for academic buildings. There are many Fitzgerald Halls at colleges and universities across the country. Next door to Fitzgerald is Tegeler Hall. The building opened in 1971 and is named after Jerome F. Tegeler. An alumnus of SLU (Class of 1929), Tegeler was a member of the Board of Trustees for many years. He had been President of the brokerage firm Dempsey‐Tegeler. There is a neat photo of Tegeler sitting in his office at Dempsey‐Tegeler in 1962 on the University of Missouri System digital library page which you can see here. The midcentury modern office looks like something off the television series Madmen. Tegeler’s son, Timothy J. Tegeler continues his father’s support of SLU. Tegeler Hall is the home of the SLU School of Social Work. The school opened at SLU in 1930; it became accredited in 1933 and has remained so ever since. The school is notable for its admission of the first African American student to the university in 1939 although formal integration of all programs and facilities would not occur in 1944. The last photo of this set is the tree-lined walkway in front of the Fitzgerald/Tegeler complex. The Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Building, or ISE, is a new addition to campus. ISE has been open for about two years, and in addition to having some modern features (as you can see in the photos), it still carries with it that new building vibe (the equivalent to the “new car smell” in my mind). The building has a large footprint and rises three stories. In total, it has about 90,000 square feet of space. Cost to complete the facility came in around $50 million. The building has LEED© Silver certification and is the second SLU structure to be so certified (the other, the Doisy Research Center, is detailed below). The building was designed by the Saint Louis-based architectural firm Hastings + Chivetta. The firm has completed numerous projects for SLU including a revision of the campus master plan. They have also designed buildings for other colleges and universities across the nation. Interestingly, one of the structures they designed was the Jonah L. Larrick Student Center on the MCV Campus of Virginia Commonwealth University where I once worked. The ISE building has a large classroom for up to 210 students, numerous instructional labs, and 10,000 square feet of research space. The contractor for the building was BSI Constructors of St. Louis. It stands on part of what was once Camp Jackson prior to the Civil War. A topping out ceremony was held on December 6, 2019. It was opened in late July 2020 and the building officially opened in a ceremony held on September 26, 2020. Situated diagonally across from the ISE Building is Ritter Hall. Although the SLU map and the sign in front of the building simply refer to it as “Ritter Hall”, the official name appears to be “Cardinal Ritter Hall”. Named for Joseph Elmer Ritter, who served as archbishop of the Archdiocese of St. Louis from 1946 to 1967. An early rendering of Ritter had the form of the building taking an “L” shape. Interestingly, it was to be part of a complex with a second structure to the east connected by a courtyard and an elevated walkway that would span Grand Avenue (see here and here). I imagine the overall cost of the complex delayed the project until such time as a different option for the site was chosen. Construction on the building began in 1965 and cost about $1.6 million (about $15.3 million in today’s value). A little over $500k of the expense came in the form of a Higher Education Facilities Act grant from the Federal government. The building was designed by the Kenneth Wischmeyer firm of St. Louis. The firm was founded by Kenneth E. Wischmeyer Sr., and later his son Kenneth Jr. joined the firm. Given that Kenneth Senior was in his eighties when the building was designed, I imagine the lead on the project was Kenneth Jr. On the south side of Ritter is the Prodigy Statue seen in the last photo of this group. I was unable to learn anything about the statue online. The next set of photos are of the Busch Memorial Center, the SLU student union. The Busch Memorial Center opened to much fanfare on September 6, 1967, delayed in part due to strikes that slowed construction. It had all of the accoutrements of a student union for the day, and much of what is standard now – an eight-lane bowling alley, a pool, ping pong tables, a cafeteria, and student organization space. Also included were a barbershop, bookstore, and a chapel. Still, reports from students that fall indicated a desire jukebox! The bowling alley was eventually removed, owing to a lack of consistent use, and the bookstore relocated across campus. The building cost $3.25 million (just over $30 million in today’s value) to build. Of that expense, $500,000 came as a donation from the Anheuser-Busch company. At the time, August A. Busch, Jr., was the chairman of the SLU Development Council. The original portion of the building was designed by St. Louis architect John A. Campbell of the Bank Building Corporation. You can see an architectural rendering of the building here. The Bank Building Corporation’s architects were responsible for some truly magnificent mid-century structures in several states. You can see some of their work archived here. Readers from outside the U.S. may know the name John Campbell from the Scottish-born architect trained at the Glasgow School of Art who was notable for his work in New Zealand. So far as I know, the two are not related. A renovation and addition to the building took place in the early 21st century. The work came in at an expense of $22 million (about $36 million today) and the building was reopened in 2003. You can see some great photos of August "Gussy" A. Busch, Jr., and Father Paul Reinert at the dedication of the Busch Memorial Center on September 27, 1967, here, here, and here. A great undated photo of inside the Busch Center can be found here. Judging by the clothes, the hair, and the wide array of cigarettes for sale (not to mention an ash tray), it would appear to be from the 1970’s. I love the size of the cash register! I had to show my sons this photo to illustrate that yes, at one point in time, smoking was widespread, and people actually paid for things with cash. Another photo seen here from about the same period or perhaps the early 1980’s shows that a bar was located in the building and beer was a measly 25 cents a glass! The first photo below shows what I believe is the original main entrance to the photo which faces north. A sunken courtyard, seen in the second and third photos graces the northeast side of the building. The courtyard features a manmade stream complete with a waterfall as seen in the fourth photo. The fifth and sixth photos are the east side of the building. In early 1966, President Lyndon Johnson visited campus during a multi-stop trip to St. Louis which also had him tour the Gateway Arch under construction. He shoveled dirt to help plant a maple tree, subsequently called the "Lyndon Tree" in front of the Busch Memorial Center. I can't say for certain, but I believe the large tree seen in the last two photos of this set are that tree. If you know for certain, please leave a note in the comments section. The next set of photos shows a group of buildings which comprise a science complex completed in the 1960's. All of these buildings sit adjacent to the Busch Memorial Center on the east side of the union. The structure seen in the first two photos is Shannon Hall. Shannon is named for James I. Shannon, S.J. who was the first head of the physics program at SLU. Shannon Hall’s official groundbreaking took place on Thursday, March 15, 1962. You can see a photo of the event here. After the groundbreaking, a benediction and remarks were given in a tent on the site (see here and here). You can also see the original rendering of the building here. STATUE INFO HERE. A couple of smaller stones which had been painted recently were located in the same greenspace as the statue of Father (NAME). One appeared to be painted about a video game (or something), but the photo I took of it was blurred. What you see here in the fifth photo is the second of these, which has been painted in remembrance of MIA Service Members. Shannon was the first structure built on what was called the Mill Creek Extension of campus. (EXPLAIN WHAT THE MILL CREEK EXPANSION WAS). Macelwayne Hall (next four) Courtyard and Monsanto Hall Monsanto received its name from the Monsanto company, which was founded in the St. Louis metro community of Creve Coeur in 1901 by John F. Queeny. The company became the first producer of saccharin in the United States. The company’s name comes from Queeny’s wife Olga Monsanto Queeny. Edwin C. Koening Plaza Below the courtyard are three large lecture halls which together can sit about 600 people. The Science and Engineering Center was dedicated in a ceremony on October 12, 1965, in the Koening Plaza. Marchetti Towers DuBourg Hall When SLU moved to its current location, the first building to go up was DuBourg Hall. Financing for DuBourg was made possible via funds made from the sale of the previous campus location. The building opened on July 31, 1888 and was for a time the only structure on campus. As such, it contained the library, offices, classrooms, a lab, and the university chapel. An historical marker by the building noted that its load bearing walls measure two feet thick! An atrium in what was then the library portion of the building extends upwards for four stories. The St. Louis-based architectural firm Chiodini Architects recently completed a renovation of the building’s interior. You can see photos of their work with details here. The building faces Grand Boulevard and the front façade stretches along 270 feet along the street. The back of the building faces the quad. Today, DuBourg is home to administrative and student support offices. DuBourg was designed by Irish-American architect Thomas Waryng Walsh. Walsh was part of the group who founded the St. Louis Architectural Association. He also began work on the design for Saint Francis Xavier Church (also known as College Church) which sits adjacent to DuBourg, but he died prior to completion of the project. Architect Henry Switzer of Chicago was brought in to finish the work. Among his other works is the St. Vincent De Paul Catholic Church in Cape Girardeau, MO which is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places. DuBourg was under construction from 1886 to 1888. It opened on July 31, 1888, the feast day of Saint Ignatius Loyola. In addition to classrooms and offices, the building also held a library which extended across the second, third, and fourth floors. The Grand Avenue side of the third floor was also home to a museum. Interestingly, you could only access part of the library’s collection which historians have described as more of general literary library as opposed to an academic library. In 1889, Henry Eils, S.J., came to SLU and spent the rest of his working days running the library. In the era before computers, books were listed on actual index cards. Eils hand wrote roughly 50,000 entries on such cards during his time. Some of those cards were still in use when the library moved to the current Pope Pius XII Memorial Library when it opened in (DATE). A thoroughly modern structure for its time, DuBourg had gas lights and was applauded for its ventilation. The building would be retrofitted with electricity in 1907. Some great old photos of the museum are available on the SLU library digital collection online. You can see a photo of the museum taken around 1888 here, and three taken in 1904 or 1905 here, here, and here. The library inside DuBourg was lavishly decorated for President Theodore Roosevelt’s visit on April 29, 1903 as can be seen here. Grand Hall Walsh Hall Formally named the Edward J. Walsh Memorial Hall, Walsh is one of three connected residence halls, although the dates of the dorms’ building were years apart. Walsh was the first dedicated residence hall on campus, opening in 1952. Griesedieck Hall Griesdieck Hall was the first mid-rise building constructed on campus. The building opened in 1964.It stands 17 stories. Griesdieck is named in honor of Alvin Griesdieck, Sr., who was chairman of the board of the Falstaff Brewing Company. His father founded the Griesdieck Beverage Company, and after serving in the Navy in WWI, he joined his father’s firm as Secretary. The company would acquire the rights to the Falstaff name from the William J. Lemp Brewing Company in 1920. The Griesdieck Beverage Company subsequently reorganized as the Falstaff Brewing Company in 1933. He became president of the company in 1938. Of the next several decades the company expanded by acquiring other breweries. He was a donor to many causes and served as Chairman of SLU’s Firms and Corporations Council. Clemens Hall Pius XII Memorial Library The third photo is a statue of Pope Pius XII by Ivan Meštrović. Meštrović was a Croatian sculptor… Readers from the U.S. may know his work at two other universities. A Pieta statue he sculpted stands in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame. A 1990 cast of his work Moses (1952) can be seen at Syracuse University in New York. You might also know his statues The Spearman and The Bowman, also known as The Equestrian Indians or The Indians, which stand in Congress Plaza in Chicago. The SLU Libraries Digital Collections have some great photos of Pius XII during construction. A photo of site work construction for the library in July 1957 can be seen here. A southward view of the first floor of the building under construction in December 1957 can be seen here. By June of 1958, the building had assumed its primary form (see here) and by that November the exterior was largely complete (see here). Samuel Cupples House It is a remarkably beautiful structure. We begin the next set with two photos of the old West Pine Gym which is home to the Center for Global Leadership. Some notable people have given talks in West Pine. Poet W.H. Auden spoke there on February 19, 1967, and Margaret Thatcher gave a speech there on May 1, 1998. Martin Luther King spoke there in 1964, just two days before being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Two nearly identical views of the building from 1952 and 1967 can be seen here and here. I love the 1961 Chrysler Imperial (easily identifiable by its tailfins) in the photo in the second link. Des Peres Hall Clock Tower Plaza The clock tower stands at what once was the intersection of (XYZ) and (XYZ) streets. Standing 50 feet, the tower was made possible in part thanks to a $2 million (about $4 million today) gift from John E. Connelly. It is in the John E. Connelly Mall. The clock tower was completed in 1993 and would receive its current name in 2011 when it was dubbed the Joseph G. Lipic Clock Tower. Lipic was an alumnus of SLU (Class of ZZZZ). Jonathan C. Smith Amphitheater Fusz Hall (with Spring Hall behind it) Museum of Contemporary Religious Art Xavier Hall (1) Wuller Hall (1) Looking Back to Clock Tower Chess/Morrissey Business Building Chaifetz First 8 or 9 Cook Hall Last Davis-Shaunessy The SLU library has a photo of Davis-Shaughnessy under construction in 1931 here. Art Museum Jesuit Hall O'Neil Hall (first two) The last three photos in this set are of Verhaegen Hall. Verhaegen is named after the first president of SLU, Reverend Peter Joseph Verhaegen, S.J. Verhaegen was not the first president in the history of the institution. That would have been Reverend Francois Niel from 1818-1824 when the institution was known as Saint Louis College. Niel would be followed by Reverend Edmund Saulnier, Reverend Charles F. Van Quickenborne, S.J., and then Verhaegen. But Verhaegen was the first president of Saint Louis University from 1832 to 1836. Interestingly, he was also the fourth and last president of Saint Louis College from 1829-1832. Born in 1800 in present-day Haacht, Belgium. His brother Pierre-Théodore Verhaegen was the president of the Belgian Chamber of Representatives (akin to the U.S. House of Representatives or the U.K. House of Commons); he is also remembered as the father of the Free University of Brussels. Verhaegen came to the U.S. in 1821 as a missionary and was ordained a priest in 1826. When Saint Louis College was taken over by the Jesuits in 1829, Verhaegen was selected as the successor to Quickenborne as president. It was during his tenure that the college received its formal charter from the state of Missouri thus becoming the first university west of the Mississippi (which was then insight from the campus). When he became Superior of the Missouri Jesuit Mission he stepped down from his position at SLU. You can view a photo of Verhaegen from 1904 here. Next, we have Saint Francis Xavier Church (or College Church). As noted above, the initial design work for the church was completed by local architect Thomas Waryng Walsh. Walsh passed away before the project was completed, and Chicago-based architect Henry Switzer eventually completed the work. The work was completed in two main stages. The lower church, the result of Walsh’s work, and the upper church conceived by Switzer. Groundbreaking for the building was on June 8, 1884. The lower church was completed by year’s end. Construction of the upper church progressed as funding allowed. The church proper was completed in 1898, although the spire would not be finished until 1914. The stained-glass windows were the work of Emil Frei Jr. Frei, a graduate of nearby Washington University, was son of German-born artist Emil Frei Sr. who immigrated to the U.S. in 1895. The family firm continues to this day with fifth-generation Frei’s at the helm (learn more about their work here. Fountain and Gate (first five) Wool Center Second fountain "The Bather) (last one) We finish our tour of the North Campus with a photo of SLU's version of the now ubiquitous lamppost sign. The next few sets of photos are of the South Campus, home to the health sciences schools and programs. The first program on the South Campus was the School of Medicine. As noted earlier in this post, medical education at SLU began in the mid-1800’s. A medical school building opened on the original downtown campus in 1853. I imagine that medical education was already in progress by this point, but I have been unable to discern when it actually began. This original medical school would separate from SLU in 1854. The medical school, now independent, was subsequently named the St. Louis Medical College. It would be led by Charles A. Pope and would colloquially called “Pope’s College”. SLU was thus out of the medical education business and would be for forty-nine years. The current School of Medicine can trace its roots back to a different institution altogether. In 1884, the local Saint Louis William Beaumont Hospital opened its own school of medicine appropriately named the Beaumont Hospital College of Medicine. I was not able to find out much about the college. It operated independently until 1900 when it would merge with another institution, the Marion Sims College of Medicine. The Sims College of Medicine opened six years after Beaumont on October 1, 1890. The school chose its name after James Marion Sims, a noted physician who has been called the “Father of Gynecology”. Sims developed many medical instruments, advanced gynecological surgery, and helped create the groundwork for the first cancer hospital in the U.S. A statue of Sims stood in New York’s Central Park from 1894 to 2018. The principal word in that last sentence was “stood”. The statue was removed due to ethical considerations of Sims’ work. He conducted surgeries on slaves and in many cases without anesthesia. His once cherished memory is now sullied by the realities of his 19th Century practices. When the Sims College of Medicine opened, 139 students from 15 states matriculated. In 1894, Sims added a dental school which would also be absorbed into SLU years later. The Sims College were located at the corner of Grand Avenue and Caroline Street the current site of the SLU hospital. When Beaumont and Sims merged, the name was changed to Marion Sims-Beaumont College of Medicine. The new combined institution would not last as an independent entity. In 1903, SLU acquired the Marion Sims-Beaumont College of Medicine. I am uncertain as the particulars driving the acquisition/merger. I have mentioned Paul Bestel’s blog America’s Lost Colleges before, and he has a great post on the Marion Sims-Beaumont Medical College here. For the most part, the SLU medical program would operate in the buildings of the former institution and would, at least at first, follow the existing curriculum. I may be mistaken, but I believe the first structure built after the acquisition was Schwitalla Hall which opened in 1921 (see below). Clinical instruction of medical students was initially conducted in the Rebekah Hospital and the SLU Dispensary. Over time, SLU would establish its own hospital and medical system. Notable among these was the Firmin Desloge Hospital which opened in 1933 (see below). Much like the North Campus, some of the entryways are marked by brick columns adorned with the SLU name. This one is located at the corner of Caroline Street and South Theresa Avenue. Two physical plant employees were about to trim the bushes when I walked up. They stepped out of the frame so I could take a photo and invited me to come back in a few minutes to get a shot of the gate in better condition. I said I would, and did mean to come back, but the heat got to me and I didn't return. Below we have two views of the Allied Health Professions Building, home to the Doisy College of Health Sciences. The school is relatively young, having been established in 1979 as the School of Allied Health Professions. The college carries the Doisy name, but the building itself does not. Edward Adelbert Doisy was a Harvard-trained biochemist. He came to the city of Saint Louis as an Assistant Professor of Biochemistry at Washington University in St. Louis in 1919. He moved to SLU in 1923 to be department chair of biochemistry. In 1930, both he and German biochemist Adolf Butenandt independently discovered estrone, but Butenandt alone would win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1939 for the breakthrough. Despite the snub, Doisy kept working and in 1943 was awarded (with Henrik Dam) the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering Vitamin K. It is a rare feat to have a Nobel Prize winner on faculty, so just imagine had he rightfully been co-awarded in 1939 giving SLU a two-time awardee who did the actual work there. Doisy and the Nobel Prize is another similarity that SLU and my former employer VCU have in common. John Fenn was awarded the 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry when he was on faculty at VCU (although I believe the work for which he received the work was completed prior to his arrival in Richmond). Baruj Benacerraf received the 1980 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He was a professor at Harvard at the time but was an alumnus of the Medical College of Virginia, now part of Virginia Commonwealth University. The first photo below is Kevyn Schroeder Hall. Schroeder Hall is home to the Trudy Busch Valentine School of Nursing. Trudy is the daughter of August “Gussie” Busch Jr., and his third wife Gertrude “Trudy” Buholzer Busch. The school acquired the Busch Valentine name after she donated $4 million in 2019. Busch is an alumnae of the school from the Class of 1980. Kevyn Schroeder was a long serving dean of the school and two-time alumnae (Classes of 1975 and 1983). You can see a photo of them together along with Valentine's daughter here. The building opened in 1978. To the north of Schroeder Hall and adjacent to the Allied Health Professions Building is statue seen in the last two photos of this set. The statue is a caduceus, the symbol of medicine. The caduceus statue here is different in that the typical presentation has two snakes and a staff, which in this case has been replaced with a woman or perhaps an angel. It is a lovely piece, particularly as it is featured with the multicolored plants at the base. I could find no information about it on the SLU website. However, it appears to be a piece by James Muir (see here), and other castings are available for purchase (see here). Below we have three views of the Education Union. When I first saw the Education Union, I thought it was simply the student union for the South Campus. Although it does have some student support services including a café, a student lounge, and a study area, it is truly an academic space. The building, which comes in at 30,000 square feet, is hallmarked by a lecture hall with seating for 225 students in stadium-styled tiered seating. The building is used by all of the health sciences programs on the South Campus. It also has exam rooms where students can engage in mock clinical work. The first two are of the east façade of the building looking to the west. The last photo is the west side of the building. This clock tower in the last photo strikes me as the bookend to the clocktower beside McDonnell Douglas Hall. Margaret McCormick Doisy Learning Resources Center SLU’s Medical Center Library is located on the second floor of the building. Caroline Building Caroline was the home the SLU School of Dentistry from 1922 until 1970. The school had formerly been part of Marion Sims College of Medicine which SLU absorbed in 1903. The program at Marion Sims was established in 1894. Schools of dentistry became increasingly common after World War II and the competition with public universities was challenging for private institutions. Amid declining enrollment, SLU decided to shutter its dental school in 1967 but allowing for graduation of existing cohorts. The school graduated its last DDS in 1971. SLU does maintain master’s programs in orthodontics, endodontics, periodontics, and pediatric dentistry. These programs are housed in Dreiling-Marshall Hall (see below). The doors you see in these two photos are not original as a photo from 1925 seen here shows a different set of them. A photo from 1952 or 1953 shows these earlier doors to still be intact, and also illustrates what the western façade of the building looked like prior to its being connected to Schwitalla (see here). Here you can see where Caroline was connected to Schwitalla. The portion to the right of the doorway marked by an indented concrete façade at the bottom is the connecting point. The cornerstone to the right marks the edge of Schwitalla. A photo from the SLU libraries digital collection from 1996 shows the connection much more clearly as the trees seen in my photo have not been planted for long (see here). Torrini Statue Schwitalla Hall The seventh photo of this series is Schwitalla Hall. It is a large building that faces Grand Avenue. Although I only captured this one photo of it, Schwitalla is an important structure on the South Campus. Schwitalla was constructed in 1921 and was subsequently expanded twice. An addition in 1927 went along Grand Avenue. An additional wing was added in 1948. This does not include the connection to the Caroline Building, nor Caroline’s connection to the Margaret McCormick Doisy Learning Resources Center. The building is named in honor of Alphonse Schwitalla, S.J., longtime faculty member, chair, and dean at SLU. Born in Upper Silesia, Germany, on November 27, 1882, Schwitalla moved to the United States with his family when he was a toddler. A two-time alumnus of SLU (Classes of 1907 (A.B.) and 1908 (A.M.), he would be ordained a priest in 1915. He subsequently attended Johns Hopkins University from which he graduated with his Ph.D. in zoology in 1921. From there, he returned to SLU as a faculty member in biology where he rose quickly to be department head. Within three years he was named Regent of the School of Medicine in 1924. He would remain in that position until 1948. He completely reorganized the school in 1927. Schwitalla was instrumental in creating the SLU School of Nursing which opened in 1928. He was a driving force for the School of Medicine and other health sciences at SLU and is generally credited with much of the expansion and success of the school and the SLU hospital during the era. He was active in the American Medical Association (AMA), especially with the Council on Medical Education. He was against government involvement in medical care, a belief that would later extend to hospitals operated by state universities. So impactful to SLU he was often referred to as the “Crown Prince of Caroline Avenue”, although some used the phrase in a derogatory fashion based on his haughty attitude as leader of the medical programs. You can see two photos of Schwitalla, the first from 1930 here and a later photo with President Holloran in 1946 here. His impact on SLU, the School of Medicine, and the SLU hospital is undeniable. He also had a significant impact on the trajectory of medical schools nationwide. Schwitalla was a site visitor for the AMA Council on Medical Education and an advocate for the elimination of two-year schools of medicine in the U.S. Two-year institutions were common in the U.S. well into the early 20th Century. The Flexner Report, or as it was titled, Medical Education in the United States and Canada, had been released in 1910 and helped to facilitate a transformation of schools of medicine into a modern format. Prior to the Flexner Report, schools of medicine were frequently independent institutions with little in the way of common standards of entrance or curriculum. Many were small proprietary schools formed by local physicians and the qualifications of graduating doctors were suspect. Among other suggestions, the Flexner Report encouraged standardization of curricula, qualifications for faculty and students, and the recommendation schools of medicine be formally associated with existing colleges and universities. Such changes were sorely needed. Well after the report, many schools of medicine remained two-year programs. In essence, these schools provided basic science instruction akin to the first two years of medical school today. Students would graduate with a certificate or other such credential and then would apply to a four-year medical school for the remainder of their education and clinical experiences. Both the AMA Council on Medical Education and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) had approved and accredited such institutions well after World War II. For the most part, graduates of these programs went on to four-year schools and excelled, and their graduation rates compared favorably to students whose entire course of study were at four-year institutions. But there was a push, particularly in the AMA group to get rid of such schools altogether. Notably, the Association of American Medical Colleges still favored two-year schools as a valid and valued part of medical education in the U.S. Two-year programs largely existed in rural states and in cities with populations too small to allow for quality clinical experiences. Two institutions come to mind in this regard: Wake Forest and the University of Mississippi. Despite both programs having long-standing success in sending their two-year students to four-year programs (for years students from Mississippi matriculated at Vanderbilt University upon completion of their studies in Oxford at such a rate that the dean of the school of medicine there at the time considered it a vital pipeline for admissions and the continued success of Vanderbilt medicine), Schwitalla and others wanted them closed. Indeed, as a site visitor for the AMA Council on Medical Education, Schwitalla had a reputation for caring little about the quality of two-year programs and was viewed as someone who merely wanted to limit the competition. A dislike for Schwitalla remained at the University of Mississippi for decades after the School of Medicine there had been transformed into a four-year program and relocated from the small town of Oxford, MS, to the state capital Jackson. Where he was lauded as a medical expert without a degree in medicine at SLU, he was derided as “a want to be, without a degree” at other institutions across the nation. I suppose there are two sides to every coin. The next to last photo in this set is another of SLU's gateways. This one stands between Schwitalla and O'Donnell Hall which can be seen in the background. Finally, the set concludes with the sign for O'Donnell Hall. SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital (three) The building you see here is the Firmin Desloge Hospital, made possible in part by a gift of $1 million from the estate of Firmin V. Desloge, II (worth about $17.5 million today). The Desloge family descended from French royalty. This particular Desloge was a successful businessman particularly in lead mining. The town of Desloge, Missouri is named after him and the mining company that carried his name. His estate was estimated to be worth some $52 million, which at just over $1.1 billion in today’s value, made him one of the wealthiest people in the U.S. at that time. The building was designed by the architectural firm Study, Farrar and Majors with engineering work Arthur Widmer of the Widmer Engineering Company. You can view a photo of the building under construction here. The fourth photo... To the left of the hospital in this photo you can see part of the building and the spire of the Desloge Chapel. Desloge’s widow Lydia gave $100,000 (about $1.75 million in 2022 value) for the construction of the chapel which had its corner stone laid on June 22, 1931. The chapel was designed by notable American architect Ralph Adams Cram. It is one of many Gothic churches he designed which includes such notables as the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York, the Saint Thomas Church (also in NYC), and All Saints Church in Boston. The Desloge Chapel was meant to evoke the style of St. Chapelle in Paris. The chapel was consecrated in 1933. Center for Specialized Medicine Doisy Research Center

Doisy, also named for Nobel Laureate Edward Doisy, is a ten-story structure that officially opened on December 7, 2007. Completed at a cost of $67 million (about $94.5 million in 2022 value), Doisy contains numerous labs and research units. deGreeff Park It is a wonderful greenspace, and I can imagine it being well used when the weather is not too hot, particularly when the youthful trees seen here grow large enough to provide usable shade.

0 Comments

|

AboutUniversity Grounds is a blog about college and university campuses, their buildings and grounds, and the people who live and work on them. Archives

May 2024

Australia

Victoria University of Melbourne Great Britain Glasgow College of Art University of Glasgow United States Alabama University of Alabama in Huntsville Arkansas Arkansas State University Mid-South California California State University, Fresno University of California, Irvine (1999) Colorado Illiff School of Theology University of Denver Indiana Indiana U Southeast Graduate Center Kentucky Murray State University Mississippi Blue Mountain College Millsaps College Mississippi Industrial College Mississippi State University Mississippi University for Women Northwest Mississippi CC Rust College University of Mississippi U of Mississippi Medical Center Missouri Barnes Jewish College Goldfarb SON Fontbonne University Saint Louis University Montana Montana State University North Carolina NC State University Bell Tower University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Tennessee Baptist Health Sciences University College of Oak Ridge Freed-Hardeman University Jackson State Community College Lane College Memphis College of Art Rhodes College Southern College of Optometry Southwest Tennessee CC Union Ave Southwest Tennessee CC Macon Cove Union University University of Memphis University of Memphis Park Ave University of Memphis, Lambuth University of Tennessee HSC University of West Tennessee Texas Texas Tech University UTSA Downtown Utah University of Utah Westminster College Virginia Virginia Tech |