University Grounds

Menu

University grounds

|

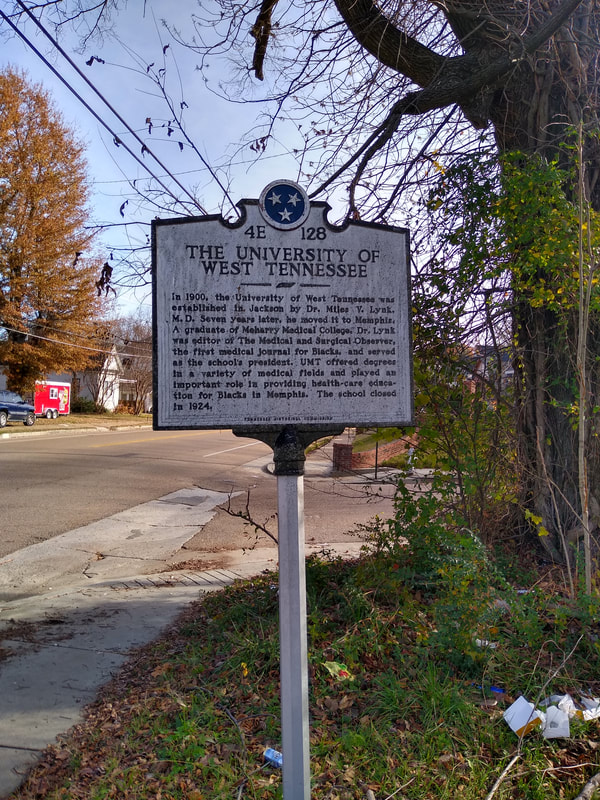

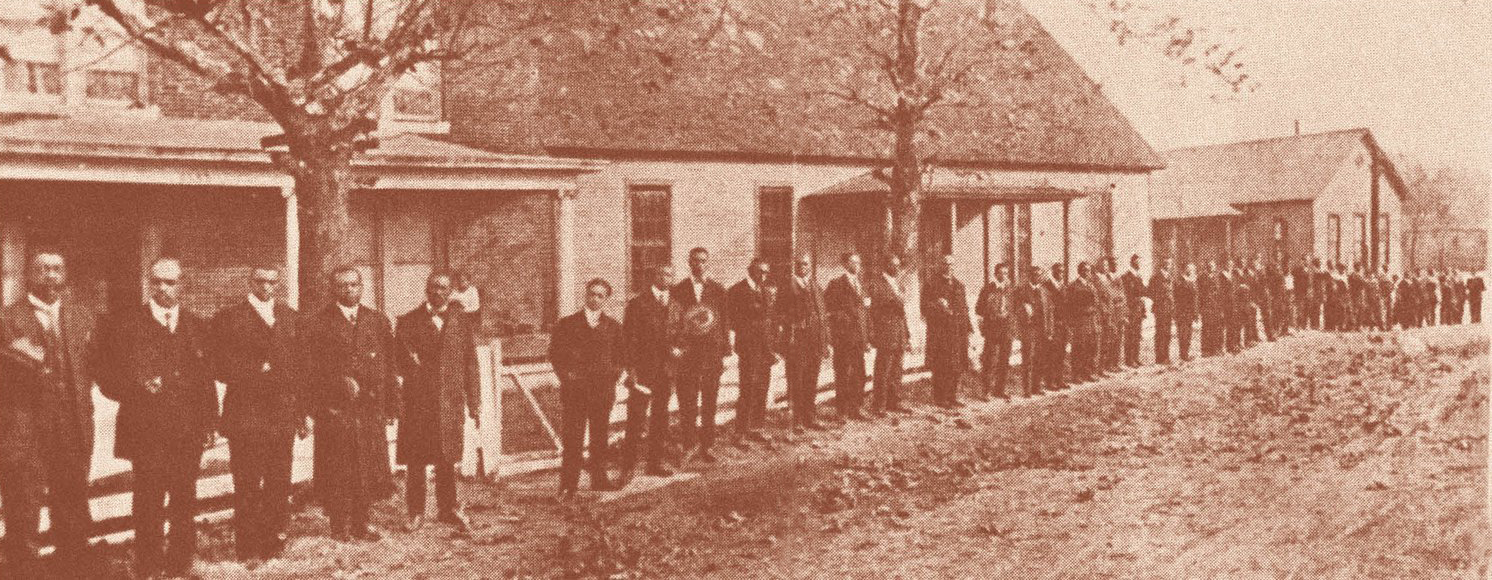

Have you ever heard of the University of West Tennessee in Memphis? I will admit that I had not until very recently. No, it has nothing to do with the University of Tennessee Health Science Center or the University of Memphis. You may not know about it as it ceased operations nearly 100 years ago in 1924. The University of West Tennessee was established by Miles Vandahurst Lynk, MD in 1900 in Jackson, TN. It would remain there for seven years until it moved to its final home in Memphis. Miles Lynk was born on a farm near Brownsville, TN on June 3, 1871. His parents were former slaves, and the family carried the name of their former enslaver, William Lynk. His father died early in Lynk’s life, but this would not disrupt his drive and desire to make a way for himself. At a time when the school year was only five months long, Lynk was able to reach the point where he passed the teacher’s examination at the age of thirteen. It was not uncommon at the time, at least for White Americans, to pass the exam and become teachers as teenagers, but his passing at age thirteen was particularly remarkable. He had the opportunity to become a school teacher in a neighboring county, but required the recommendation of White man. He approached William Lynk but was fiercely rebuked. This refusal cost him the opportunity, but he would not be denied. He continued his education despite his age, paying for tutoring in the absence of available formal education. He would enter the Meharry Medical College in 1889. The program at Meharry was two years at the time, and Lynk graduated on time in 1891. He subsequently moved to Jackson, TN and opened a practice. It was there he met twenty-year-old Beebe Steven, a recent graduate of Lane College. They were married on April 12, 1893. Beebe would prove to be an equal to Miles. She wrote her first book, Advice to Colored Women, in 1896. Together they would go on to found the University of West Tennessee, establishing a host of firsts and breaking down barriers as they went. I will begin this post with the historic marker for the university. Interestingly, the sign is not at the former location of the university, but rather sits a couple of blocks away at 785 East McLemore. McLemore is the major street in the area, and perhaps that is why it is located there. It is also interesting to note that the historic marker has a typo on it. Note that it refers to the university as "UMT". I imagine the letter was simply flipped from a "W" to an "M" by accident and no one noticed until the sign had been erected. Dr. Lynk was thinking big from the time of his graduation from Meharry. There were needs he wanted to address and from all appearances he did not hesitate to take action. He started the very first African American medical journal, the Medical and Surgical Observer in 1892, only two years after completing his studies at Meharry. Despite a warm welcome from the Black medical community, the publication did not last. The publication ceased after just over a year in 1894, apparently due in part to the cost of the operation and the subsequent fees for subscription. Still, it was the first, and Lynk’s push certainly fueled the fire for the journals that would follow. Later, Lynk would be instrumental in creating the National Medical Association, the African American alternate to the American Medical Association which, to that point, excluded African Americans from membership. Miles and Beebe then set out to create their own medical school. Their determination had them take out a second mortgage on their home to acquire the necessary start up funds. They were able to get the institution chartered in 1900 with the name the University of West Tennessee College of Medicine and Surgery. It was at this point that Lynk did something a bit unusual, at least for most people who were practicing physicians who were simultaneously founding a medical school. He went to law school. Actually, that’s not exactly correct. There was no school for African Americans wishing to study law in Jackson at the time. Rather than study under a practicing attorney, which was a common practice at the time, Lynk helped Lane College develop a law department. He began his studies in 1900 and graduated in February of 1901. He passed the Bar Exam later in the month. Although small, UWT would begin enrolling students and almost immediately began expanding. Almost as soon as the school had opened it expanded to include a dental school, law school, and a school of pharmacy. It was from this latter school that Beebe would obtain her PhC (Pharmaceutical Chemist) degree in 1903. She would then become a member of the UWT faculty. Owing to the need be in a larger, more accessible, and financially supportive community, UWT moved to Memphis in 1907, establishing itself in two structures at 1190 South Phillips Place. By the time it was located in Memphis, the school would be known simply as the University of West Tennessee (I am uncertain as to when it changed its name). Students would come from across the U.S. and internationally. Indeed, José Antonio Price, the first Black physician in Panama, was a graduate of College of Medicine's Class of 1913. You can see a copy of the 1910 UWT catalog here. In addition to noting the courses, faculty, and other information, you will see that at the time UWT was located in "two commodious and well arranged buildings, known as North Hall and South Hall" (p.5). Although the information varies from source to source, most agree that at least 216 physicians would graduate from UWT over the course of its existence. That is a very large number of graduates for the era. The number of African American physicians in the U.S. grew rapidly during the period from 1890 to 1920. Indeed, research indicates that the number of Black doctors grew more than 384% nationwide during that period (Savitt, 1987). There were fourteen African American doctors in Memphis in 1890, but by 1920 there were 83 thanks in no small part to UWT (Savitt, 1987). Those numbers may seem small, but keep in mind that the population of Memphis in 1920 was only 162,351 (and the city really didn’t have much in the way of suburbs so the total metro population would have been little more). Atlanta had a mere 41 African American physicians and New Orleans a paltry 30 at the same time. Only Saint Louis, MO, and Washington, DC had more Black doctors than Memphis. It should also be noted that Nashville, in no small part thanks to Meharry, had 68. Thanks to schools like UWT and Meharry, Tennessee had 327 African American physicians in 1920, which was more than any other Southern state. By comparison the next closest states were Georgia, which had only 228, and Texas, which had 217. This despite the fact that both states had a larger total population than Tennessee (Black or White). Put another way, during its brief existence, UWT graduated nearly as many doctors as were in practice in Texas in 1920. That is quite the feat! The two photos below are, as far as I know, in the public domain. If you happen to be the copyright holder please let me know and I will gladly take them down. The first photo below is of the faculty and some of the students at UWT in 1915. I say some of the students as there were women enrolled in the institution in 1915 and none are present in the photo. Hence, these are only some of the enrolled students. These are North and South Hall, although I cannot say which is which. I believe Dr. Lynk is the second person on from the left. The second photo, which is also on his headstone (see below), is Dr. Lynk later in life. You can find photos of him online. As a young man, he wore a large, thick moustache common in the Victorian era. Over time, the moustache got smaller and at some point disappeared altogether. I went over to take a photo of the site where the buildings once stood. I believe the streets have moved since that time. Google maps shows a spot that is not actually on South Phillips but one street over on Fountain Court. The houses on Fountain Court now back on to South Phillips. South Phillips is a one lane street (more like an alley), and although the street is generally accessible, the block where UWT would have stood is quite overgrown and, regrettably, used as a dumping ground for all sorts of trash and debris. I am uncertain as to which side of South Philips the university's buildings stood. My best estimate is that the structures stood generally in the area you see in the photo below. To the left just beyond the trees are the back yards of the homes on Fountain Court, and to the right is either the back yards of the homes on Krayer Street, or vacant lots on South Philips. I took the photo looking south straight down South Philips. I would have taken photos of either side, but I would be essentially taking a picture of the back of someone’s house which, in addition to being a bit rude, would have undoubtedly looked suspicious. I show UWT's former location on the map below. As far as I can tell, there is no sign of the university at its former location. The two structures mentioned in the university’s catalog and seen in the historic photo above were apparently demolished long ago. Some foundations could be hidden in the overgrowth to the right in the photo, but having looked around as best I could I didn't find any. There appears to be nary a trace of UWT at its former location. Despite the historic marker, I would venture a guess that many of the people who live in the area currently are unaware of its existence. About eight miles to the south (about six and a half miles as the crow flies) is the final resting place of Drs. Miles and Beebe Lynk in the New Park Cemetery. Since there was little to show of the university, I thought I would stop by and photograph their memorial. The very helpful young lady in the office directed me to the area of the grounds which holds their grave and I located it with ease. Their headstone, seen below, was apparently given to them by their former students. For those who would care to take the pilgrimage, I have noted the location of their plot on the map below. Reportedly, the ultimate cause of death for UWT was the combination of financial issues and the impact of the Flexnor Report. As I noted in my previous posts on Saint Louis University and the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the Flexnor Report called for the establishment of base standards for all medical schools, their faculty, curriculum, and methods, a training period of four years on-site, and for the connection of medical schools with established four-year colleges and universities. Although not immediate in terms of resulting in the closure of two-year medical schools, the report’s recommendations would be accepted, and the standard would come to be the norm in the years following its publication. UWT was not a four-year program, and given its small size and independent nature, making the transition would have been very difficult. As it happens, UWT was one of the institutions Flexnor visited and he gave it low marks for facilities and other items. If its demise was caused, or at least hastened, by the Flexnor Report, UWT would not have been alone in being the victim of the new standards. Dozens of medical schools – HBCU’s and historically White institutions alike – closed in the years after the report. HBCU's were the hardest hit, however. Prior to the Flexnor report there were fourteen HBCU schools of medicine in the U.S.; today there are only two (Howard and Meharry).

At the time, there was no local potential partner that could have save the institution or at least delayed its demise. The University of West Tennessee was located about three blocks from the current site of LeMoyne-Owen College, a small HBCU which has its founding date in 1871. It remained a K-12 and vocational school until 1924, when it became a junior college offering the two-year degree. At the time, the then-named LeMoyne College was not in a financial state to truly aid UWT and it lacked the four-year baccalaureate offerings needed under the new medical school standards. The timing was unfortunate. A mere three years after UWT close, LeMoyne would move to offering a traditional baccalaureate curriculum. Of course, it likely still lacked the financial resources to aid UWT in pursuing the other requirements of modern medical education, so even if the transition had happened earlier, it seems unlikely that the medical school would have continued. But imagine if you will an alternate history where the two somehow managed to stay afloat and merge sometime in the late 1920’s or early 1930’s. Memphis could have become the home to a larger, more robust HBCU complete with a range of health sciences offerings and a law school. The combined institution could have come to rival Meharry in Nashville. Memphis could now have three medical schools instead of two (Baptist Health Science University recently opened a school of osteopathic medicine and of course the University of Tennessee Health Science Center has its MD program). It could have meant a lot for Memphis, the African American community, and the region. Of course, much would have had to happen for this to have actually taken place, but its fun to dream about such things. If you'd like to learn more about Miles and Beebe Lynk and the University of West Tennessee, I'd encourage to read a number of sources. Karen Sarena Morris completed a thesis as part of her MD program at Yale University entitled The Founding of the National Medical Association. Ashley Grizzard Geisewite completed an entire dissertation on Miles Lynk (Miles Vanderhurst Lynk: A Pioneer for African American Medical Higher Education in West Tennessee) when completing her doctorate in Higher and Adult Education here at the University of Memphis. You can also read a number of journal articles including the following: Harley, E.H. (2017). The forgotten history of defunct black medical schools in the 19th and 20th centuries and the impact of the Flexner Report. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(9), 1425–1429. Savitt, T.L. (1996). 'A journal of our own': the Medical and Surgical Observer at the beginnings of an African-American medical profession in late 19th-century America. Part one. Journal of the National Medical Association, 88(1), 52-60. Savitt, T.L. (1987) Entering a white profession: black physicians in the new South, 1880-1920. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 61(4), 507-40. Lynk wrote an autobiography (Lynk, Miles V. (1951). Sixty Years of Medicine: Or, The Life and Times of Dr. Miles V. Lynk. Twentieth Century Press), but I have not been able to my hands on a copy. You can also view a short video on Lynk produced by the TriState Defender on YouTube here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AboutUniversity Grounds is a blog about college and university campuses, their buildings and grounds, and the people who live and work on them. Archives

May 2024

Australia

Victoria University of Melbourne Great Britain Glasgow College of Art University of Glasgow United States Alabama University of Alabama in Huntsville Arkansas Arkansas State University Mid-South California California State University, Fresno University of California, Irvine (1999) Colorado Illiff School of Theology University of Denver Indiana Indiana U Southeast Graduate Center Kentucky Murray State University Mississippi Blue Mountain College Millsaps College Mississippi Industrial College Mississippi State University Mississippi University for Women Northwest Mississippi CC Rust College University of Mississippi U of Mississippi Medical Center Missouri Barnes Jewish College Goldfarb SON Fontbonne University Saint Louis University Montana Montana State University North Carolina NC State University Bell Tower University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Tennessee Baptist Health Sciences University College of Oak Ridge Freed-Hardeman University Jackson State Community College Lane College Memphis College of Art Rhodes College Southern College of Optometry Southwest Tennessee CC Union Ave Southwest Tennessee CC Macon Cove Union University University of Memphis University of Memphis Park Ave University of Memphis, Lambuth University of Tennessee HSC University of West Tennessee Texas Texas Tech University UTSA Downtown Utah University of Utah Westminster College Virginia Virginia Tech |